Outdoor Ed tussles with F-stops and grad filters as Chiz Dakin takes him through the basics of landscape photography

Ed Byrne is currently touring Britain with his new show, Spoiler Alert, as part of which he shares some hilarious insights into the trips he’s made into the hills for The Great Outdoors magazine. To celebrate, we are publishing one of his archive features each week as a treat for Ed’s fans and readers of The Great Outdoors.

It’s called ‘The Golden Hour’, that time around either dawn or dusk when the sun is low in the sky and the light streams across the land, creating long shadows and bathing the scenery in an amber glow, giving the world a magical tint that the photographer just needs to press a button to capture. That’s the idea anyway. But in the Peak District, when the fog rolls in, it doesn’t matter what time of day it is – everything looks like you’re trying to view it through a steamed-up window.

I meet up with Chiz Dakin, co-author of the Cicerone guide to outdoor photography, hoping to get a few tips to help me capture some of the beauty I’ve been exposing myself to since I started venturing forth into the great outdoors. (By ‘exposing myself to’, I mean experiencing. I don’t mean I’ve been standing naked on the side of a mountain.) I’ve read a few books and magazines about the art of landscape photography but, like tying knots or French kissing, it’s one of those things that you really need somebody to physically demonstrate in order to have it properly enter your head.

there’s something very appealing about listening to a woman almost have an argument with a camera like it’s a work colleague rather than a tool of the trade

The first thing to consider is your location. We head to Stanage Edge in the hope that the fog will have cleared and also because, Chiz tells me, it catches the sun very nicely at sunset. She then goes on to explain that the shape of the landscape is only part of what makes it photogenic. A major factor is what direction it’s facing in relation to the sun during that golden hour. This never occurred to me, but I suppose it makes sense. While a model can turn her head to make sure you get her good side, a cliff face can’t. I suddenly feel sorry for all those hillsides that you think are beautiful but don’t face the right way so never seem to be worth photographing… like the girl next door who was beautiful but just not tall enough to have a career on the catwalk.

Chiz demonstrates the effect of the angle of light on the subject by having me take three photos of the same rock from three different angles relative to the sun: one with the sun behind me, one with the rock between me and the sun, and one with the sun on my left. The difference was quite obvious even in the cloudy conditions we were experiencing. With the sun behind me the rock looks flat and dull. When the rock is between me and the sun, it’s virtually silhouetted but when the sun is on the left, the details of the rock are picked out by light and shade. Pretty simple.

Then we start to get a bit more philosophical. Chiz asks the question: “What do you want the photograph to say?” This is an easy one. I want the photograph to say: “Isn’t Ed Byrne good at taking photographs?” I don’t think this is the answer Chiz is looking for so we move on to more technical matters. We have a chat about exposure and how the camera has to make a guess at how much light it should let in, depending on the brightest and darkest parts of the scene in front of it. While our eyes and brains are constantly refocusing and editing together everything we’re seeing without us really noticing, a camera isn’t as clever as we are. But they are pretty clever – sometimes they can do everything automatically, sometimes you have to adjust some things manually and let other things happen automatically, and sometimes you have to set everything manually. As Chiz explains how the camera works she does something I find quite endearing. She personifies the camera and has a sort of dialogue with it.

“So the camera looks at the brightest bit and says: ‘That’s supposed to be this bright, I’ll adjust myself to suit that,’ and you might say: ‘No. That’s too bright.’ And you have to tell the camera: ‘I know you’re normally quite good at this, but I need you to go a bit darker.’ So you adjust it again, and the camera says: ‘Oh, I see what you mean, you want it like this,’ but it’s still not right and eventually you have to say: ‘Sorry, you’re still not getting this. I’ll have to adjust everything myself.’”

I’m not really doing it justice, but in the same way that sailors personify their boats and call them women’s names, there’s something very appealing about listening to a woman almost have an argument with a camera like it’s a work colleague rather than a tool of the trade.

- Check out Dougie Cunningham’s feature on choosing a camera for outdoor photography

The next technique Chiz shows me is how to use a graduated neutral density filter, which sounds a lot more complicated than it is. It’s a piece of glass that’s dark at the top and clear at the bottom that you hold in front of the camera in order to darken the sky and so make the land seem brighter. A perennial problem in landscape photography is that the sky is quite bright and the ground relatively dark, so either the sky ends up over-exposed or the land ends up under-exposed. A filter held in front of the camera, darkening the sky, fools the camera into doing what our eyes and brains do naturally. I have since bought one and it works a treat.

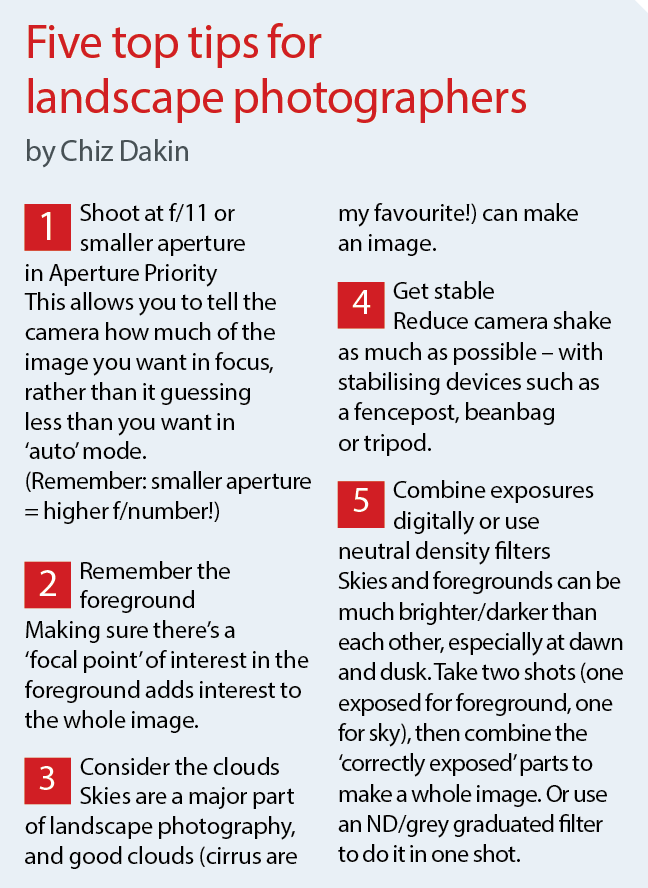

Then things start to get a bit more complicated. Chiz starts showing me how your depth of field changes as you adjust your aperture. To put it another way, if the aperture is narrow (higher f-numbers), more things are in focus at the same time. If the aperture is wider (lower f-numbers), not everything is in focus, helping to highlight the specific part of the scene you want to draw attention to. That much I understand, but as Chiz goes on to talk about what aperture setting you should have depending on the focal length of your lens and the distance from your subject, my brain just begins to overflow. You know that point in a phone conversation when you’re not really taking all the information in and you have to say to the other person: “Can you put all of this in an e-mail and send it to me?” That’s the point I had now reached.

The sun had by this time gone down and the cameras were beginning to pick up a lot of condensation so it was time to call it a day. A miserable day. I headed back to my car with a head full of tips and hints and a shopping list of camera gear to go in my letter to Santa Claus.

This feature was first printed in The Great Outdoors, February 2012.

Images of Ed Byrne © Chiz Dakin peakimages.co.uk