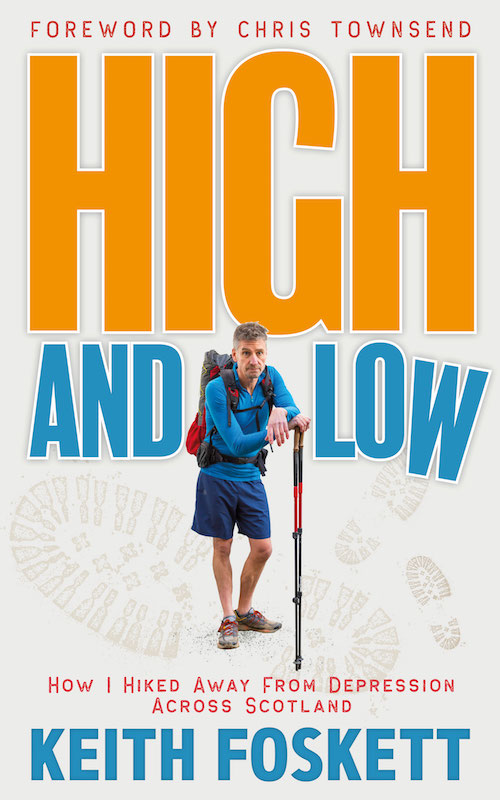

An exclusive extract from Keith Foskett’s new book, High and Low, exploring the complex relationship between depression and the outdoors

High and Low is the new book by acclaimed outdoor writer Keith Foskett, author of several books on long-distance backpacking. With a foreword by Chris Townsend, this book tells the story of how Keith Foskett came to realise that his experience in the outdoors was interwoven with depression – but he found a way to fight it.

Could the Outdoors Cure my Depression?

By Keith Foskett

The first place I retreat to is the outdoors. It’s my failsafe, my escape, where my head quietens and, slowly, I relax and regain composure.

We live hectic lives with work and family commitments, and with the advent of social media, I regularly find myself hitting overload. Throw depression into the mix and I often run to the hills.

But, could the outdoors cure my depression? In a word, no.

During the summer of 2016, I fled north to hike across Scotland, a dream I’d nurtured for years. I knew my life was in turmoil and I needed refuge in this glorious corner of Great Britain. What I didn’t know was I’d been suffering with mental illness for years, and I’d been oblivious to it.

For 600 miles, while trying to understand why I was so angry, I battled relentless storms, overwhelming midges, and my inner demons.

Hiking and depression are rarely mentioned in the same breath. Any subject and depression are rarely mentioned. I never talked about my mental illness until someone suggested we need to tackle the stigma surrounding it. Depression is misunderstood, and we fear others won’t understand what we are battling.

When I opened up, the first time I started to talk was when I hiked with others. Being outside, the sun on my arms, the clean air and feeling of space made it the ideal environment to talk. More often than not, I wasn’t judged, but accepted.

The outdoors didn’t cure my depression, but the events that happened in Scotland pointed me in the right direction to realise I was suffering from mental illness. It is where the healing began and carries on now.

Exclusive Extract from High and Low

I slept well, despite the early sunrise illuminating my tent. Then I realised.

Hang on a sec, the bloody sun’s out!

At the end of my trip, out of curiosity (and slight resentment), I calculated how often it had rained. Of the 31 days I took to traverse Scotland, 29 of them had been wet. This is not conducive to a healthy state of mind. As Nick Levy, a friend with whom I hiked part of the Pacific Crest Trail, said: “You can push through many obstacles with determination, but the hardest is poor weather. It’s belligerent – it will break you eventually.”

I unzipped the tent and peered out, squinting at the intense light bouncing around Glen Coe. I escaped from my sleeping bag and stood to soak it up.

Oh, you got to be kidding me! This is fantastic!

At that precise moment I remembered I hadn’t spent the night somewhere remote and hidden from view. In fact, I was 100 feet from one of the busiest roads in Scotland, and stark naked.

At that precise moment I remembered I hadn’t spent the night somewhere remote and hidden from view. In fact, I was 100 feet from one of the busiest roads in Scotland, and stark naked.

As I suddenly realised this fact I caught sight of a woman speeding past in the passenger seat. I followed her eyes as they met mine; they moved downwards and paused, longer than was necessary. She screamed with surprised laughter before turning to relay the news to the driver, and then the car vanished behind a hillock. My hands dropped as I dived back in the tent to put my clothes on.

Scotland had changed dramatically. The sky was an intense, cloudless blue. Huge banks of mist floated through Glen Coe, creeping between Stob Dearg over the far side of the valley and Beinn a’ Chrulaiste behind – spectres riding the weakest of breezes, passing and eyeing me cautiously. The temperature dropped a few degrees as these spirits passed, then rose as the sunlight broke through again. Like theatre curtains opening and closing for several, well-deserved encores, Scotland vanished then reappeared, bowing. The ghosts of Glen Coe themselves had engulfed me.

I made coffee, then tipped dried milk powder into my pot with water and stirred, added granola, crumbled in some dark chocolate, and drizzled it with honey. Sipping my drink and munching my breakfast, I nodded the occasional greeting to hikers, who seemed surprised I had camped by the side of the road.

“Fozzie! I caught you!”

I turned my head in surprise, shocked that Elina had arrived so fast.

“What are you doing here so quick?” I cried from a mouthful of granola. “Sorry, I have food in my mouth!”

“I can see!” She removed her pack and sat beside me, rummaging around for a snack. “Well it is 10.30.”

I checked the time in disbelief; having only been up 30 minutes, I must have woken at 10.00. I’d slept for 12 hours straight. Before I could fathom how, she continued.

“The taxi dropped me back to Kinlochleven at 8.30. I’ve been walking since then. Why did you camp here? What about the cars?”

“I got off the Staircase late, and the trail sticks to the road for a while yet. I was tired, so I stayed here. Not ideal but surprisingly quiet.”

“Look at this sun, it is warm, and bright! So bright!” She screamed in delight.

I watched as she strolled, pausing to hold her face up, arms outstretched. She looked elated, and for a second, ashamedly, I was jealous. It was simple; she was happy, I wasn’t. How had this girl overcome her demons and escaped her torment to be the woman I saw now? I suppressed a feeling of unfair resentment and pondered how I could liberate my own anxieties.

“Fozzie! Come on! Let’s go! I want to walk through Glen Coe!”

I flitted between packing, smearing sunscreen on my face, and trying to find my socks.

In hindsight, if I’d digested what she had been telling me, and followed the trail of clues, I might have realised earlier

“OK! Ready!” I cried, smiling in anticipation. “Let’s do it!”

We’d only managed an hour’s hiking when the Way Inn appeared.

“I need coffee,” Elina declared.

“Me too,” I replied. “Oh, look at that, they’re doing cooked breakfast.”

“You just ate!”

“That was at least an hour ago.” I rubbed my stomach. “Besides, firstly, never, ever pass up a cooked breakfast, and second, we should talk.”

She raised her eyebrows, appearing confused, and smiled.

We placed our coffees on a table, spoons chinking as sunlight caught the rising steam. Elina sipped on her coffee and sighed in appreciation.

“Do you mind telling me more about your depression?” I asked her. “You don’t have to if you don’t want to.”

“It’s fine, Fozzie, I’m happy to. I hadn’t been right for a year but thought I was just down a little. There were horrible periods towards the end of that time – over the course of a few days I cried uncontrollably, sometimes shaking for no reason. I didn’t want to see anyone or work. I said I had a cold and hid from everything for a week.”

She peered out of the window, glanced my way, and smiled. I sensed there was more coming.

“A friend called. I told her everything that was happening. She ordered me to go to the doctors that afternoon and to tell them I might be suffering from depression.”

“How did she know?” I asked.

“Because she suffered with the same thing.”

“What did the doctor say?”

“He asked me a lot of questions, about sleep, if I drank alcohol or took any drugs. He wanted to know how I felt about life, my future, how I coped with my job and other people. I think these questions gave him an idea of if I had depression, like a checklist. He recommended pills, I forget name.”

“He asked me a lot of questions, about sleep, if I drank alcohol or took any drugs. He wanted to know how I felt about life, my future, how I coped with my job and other people. I think these questions gave him an idea of if I had depression, like a checklist. He recommended pills, I forget name.”

“Antidepressants?”

“Yes, those. I said no, so he strongly suggested that I stop smoking marijuana, cut my drinking if not stop altogether, and concentrate on looking after myself. He put me in touch with a counsellor. Fozzie, do you think you—”

I cut her off. “No, I’m not depressed, just down that’s all.”

“There’s no shame in it. If you’re unsure, see a doctor.”

“Yeah, OK.”

We finished our bacon rolls, walked out into the Scottish sunlight, and carried on south. As if the topic had been resolved, we talked about other things. The path was busier; hikers passed every few minutes nodding, smiling, and offering greetings. They were happy, out enjoying Scotland in beautiful weather.

It was strange. My situation couldn’t have been more different a few days earlier. I thought back to when I’d left the Cluanie Inn, climbed into the clouds, walked in rain for most of the day, crossed rivers, and saw just one person. Now, I had a companion and conversation, I’d passed many hikers, I was wearing shorts and a T-shirt, and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. Instead of wanting the trail to be over, I hoped it would last forever. It was limitless Guinness, but I wanted endless mileage as well.

Although curious about the discussion with Elina, I believed I was OK. In hindsight, if I’d digested what she had been telling me, and followed the trail of clues, I might have realised earlier.

It’s hard to explain, Fozzie, and to understand too, but for me, there are many mood swings.

I get low, really low. So low that I cry.

Depression isn’t voluntary, we have no choice.

There’s no shame in it.

High and Low is out now in paperback and e-book.

Full disclosure: TGO’s Online Editor, Alex Roddie, edited this book.