Mark Waring spends time exploring the High Arctic wilderness of Svalbard.

In our September 2018 issue, you’ll find our 35-page Scandinavia Outdoors supplement, which aims to demonstrate that Norway, Sweden and Finland can justifiably claim to be home to Europe’s best backpacking.

We’ve selected some features on Scandi backpacking from our archives, and over the coming weeks we’ll be republishing them online in full for the first time. In this excellent and atmospheric piece, Guest Editor Mark Waring explores Svalbard – which isn’t your everyday backpacking destination.

Check out our other digital features in Scandinavia Outdoors.

Ten Long Days in the Arctic by Mark Waring

This feature was first published in the May 2015 issue of The Great Outdoors.

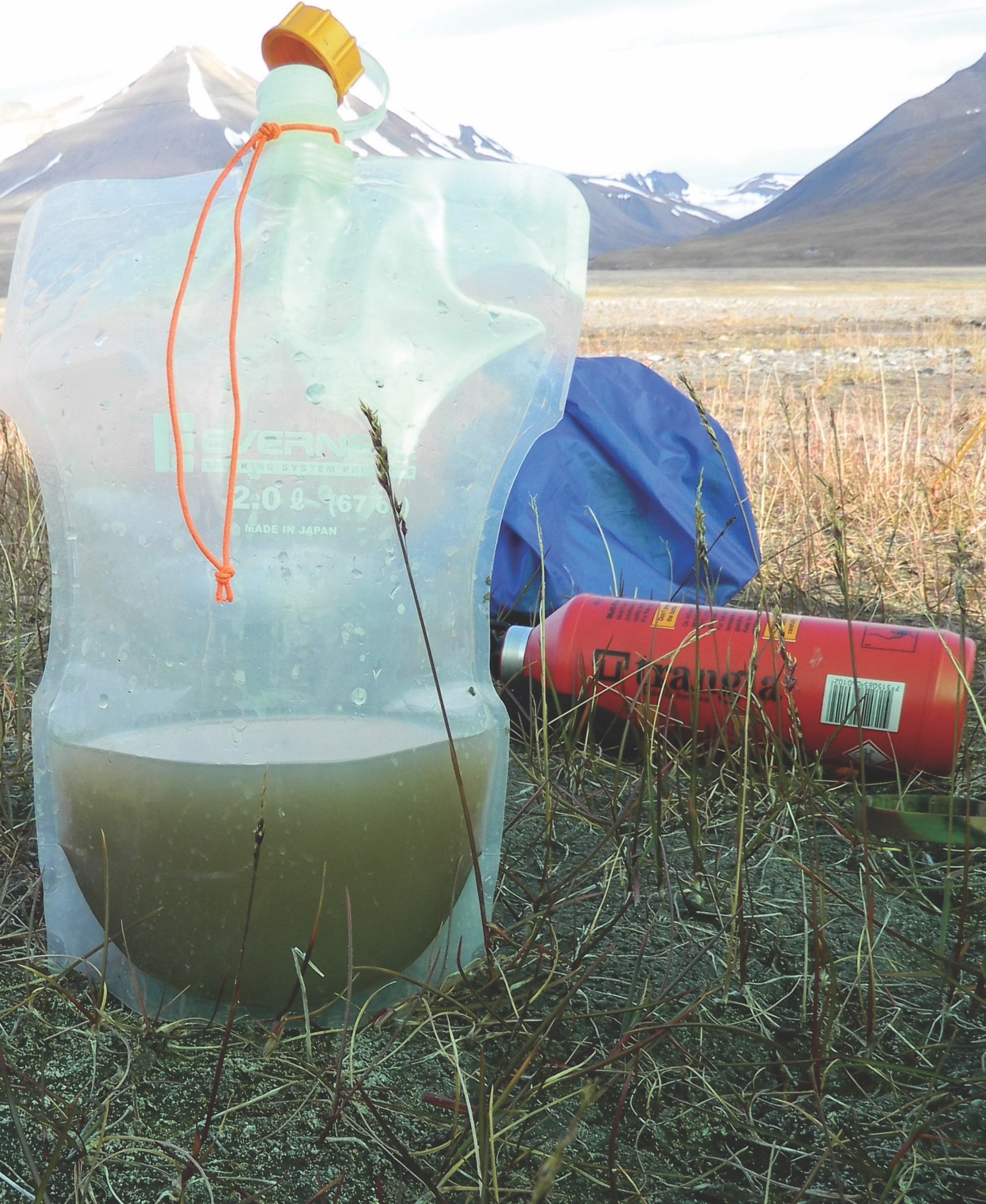

I lay my rifle gently on suft tundra and bend down to fill a water bottle from the grey waters of Adventelva. A flash of sunlight on metal causes me to pause. The cloud breaks and the high polar sun flares, first on a vast satellite dish sat on a mountain top above and then, in a beat, against one of four metal posts that guard my tent. Setting camp that first night in the midst of High Arctic wilderness, I reflect on the advice of a seasoned Svalbard expedition leader. “This place is exceptional”, Chris Searston of Ice Bear had promised, “and so are the steps you take to travel through it”.

Svalbard has many names. Try perhaps ‘Spitzbergen’ or even the Russian ‘Шпицберген’ to describe the lonely islands of ice and rock on the fringes of European civilisation. Svalbard lies midway between the northern tip of Norway and the North Pole itself, the southern extremis of the High Arctic. With no indigenous population man’s presence is relatively recent in a land that falls into black winter for an entire three months. Pertinently, as would-be travellers are advised, this is a place where nature is dominant. Polar bears range wide, outnumbering human occupants by a sobering ratio of three to one.

Meltwater meandering through Upper Adventelva

© Mark Waring

Despite that, Svalbard presents an intriguing destination for the adventurous. The islands have drawn man since the Dutch explorer Barents stumbled across Svalbard in 1596. Reeling from the violent death of one of his crew at the claws of a polar bear on an outlying island, Barents sighted a land of high mountains, glaciers and beaches locked in sea ice in June. A summer blizzard couldn’t quite obscure the characteristic jagged spires of the islands and Barents landed, the first man on Svalbard.

News of discovery and the promise of abundant resources brought first the whaler and then the trapper. Next the prospect of coal established the permanent presence of industrialising European nations. Science brought others, and a legacy stands to this day of research stations studying climate change as well as the home of the ‘Doomsday Vault’ (the International Seed Bank is a repository of four million crop varieties deep in the bowels of a Svalbard mountain as a means to protect bio- diversity). Svalbard set a stage too during the ‘golden age’ of polar exploration at the turn of the 20th century as nations competed for polar firsts and the mercantile advantage of the fabled ‘North-West’ and ‘North-East’ passages. Many expeditions were launched from the capital, Longyearbyen, and whether they floundered or triumphed, men such Franklin and Amundsen were elevated to a celebrity status that mirrored growing fascination with the North.

As the 20th century progressed, Svalbard sat on a fault line of geo-politics. Norway is ceded sovereignty by treaty but signatory nations can exercise economic rights. Russia cements a presence with two remote towns, sentinels of a region she sees as hers and a springboard to this day to vast natural resources. Rumours abound in Longyearbyen of elite soldiers and heavy weaponry secreted in the Soviet mining towns, and cold war intrigue is rife.

High in the Arctic

I’ve arrived in the relative warmth of an Arctic summer for a ten-day backpack into Svalbard’s interior and then along its coasts, visiting its remaining living Russian enclave.

Despite ice covering two-thirds of the islands there’s good hiking for the prepared in a wilderness of mountains, glaciers, tundra and empty Arctic beaches.

I’m drawn too by the poignant monuments to several hundred years of human visitation – old trappers’ huts tucked into lonely valleys or whaling camps hidden in remote bays. The crown jewel of this splendid desolation is a crumbling Soviet town called Pyramiden, deserted on the orders of the Russian mining company. Deemed uneconomic, the Russians abandoned a compact settlement complete with sports centre, library, hotel, school, imported Siberian grass and the most northerly bust of Lenin. Workers were ordered to leave in a matter of days, the town left to slow decay and passing bears.

“A .308 rifle is the last line of defence if a bear encounter goes wrong. I arm the rifle by setting the bolt into it and move forward, somewhat tentatively.”

As I pick my cases from the luggage carousel at the airport in Longyearbyen that bright August night, I reflect. Technically I’ve not left modern Europe but the place feels different. Bright sun in the early hours, a mix of voices including Russian and imagery of the polar bear everywhere. My bag is particularly heavy, carrying as it does specialist equipment, an imperative to protect myself. It is no exaggeration to state that polar bears are common in Svalbard and that they are a considerable threat to people. Managing that risk is key.

Two days later I leave the assurance of Longyearbyen, with a long trek before me. The plan’s a fairly simple one: a circular tour of Nordenskiold’s national park through some of the long glacial valleys until I emerge on the coast before a night’s stop at the living Russian mining colony of Barentsburg. Thereafter a three-day walk back to Longyearbyen, a high route over the hills that screen the town and finally down to its safety.

It’s a comfortable distance of around 130 kilometres over ten days, but due to the nature of the terrain and the weight on my back I’ve been warned of a very tough hike indeed.

Rifling matters

I’m carrying a lot of extra equipment, including a high-calibre hunting rifle and a trip-wire fence. Locals and tourists alike are encouraged by the authorities to only leave the settlements if armed. A .308 rifle is the last line of defence if a bear encounter goes wrong. Additionally, I’m to use a warning fence, bought from the British company Ice Bear and I’ve benefited too from the extensive Svalbard experience of its MD Chris Searston. A safe Svalbard trip is about setting a defensive camp with a good quality warning fence. The fence essentially strings four trip-wires around camp connected to an alarm mechanism. The Ice Bear fence employs four firing mechanisms which trigger a blank shotgun cartridge when pressure on the trip-wire pulls the firing pin out of the groove. The resulting bang should either alert the camp or possibly scare an intruder.

Setting the bear fence

© Mark Waring

The rifle came everywhere

© Mark Waring

Longyearbyen’s boundaries are marked by a sign warning of bears beyond; stepping past and out into the long glacial valley of Adventelva feels significant. I arm the rifle by setting the bolt into it and move forward, somewhat tentatively.

That first night sees an early camp in Adventdalen; as I get to grips with setting the fence around my perimeter, I’m conscious at all times as to where the rifle is. Man’s presence is still obvious. The furthest of Longyearbyen’s mines dot the hills. At the onset of the 20th century, Svalbard was still a no-man’s-land, and the first years were chaotic as people scrambled for wealth. Flamboyant and unsound industrial adventures abounded and the majority failed, their legacy century-old buildings and machinery in pristine Arctic landscape. Towering over them tonight are two large satellite dishes, now mining only the secrets of the Aurora Borealis.

“Down one final lonely corridor I go, 20 bedrooms deep, until I emerge blinking into bright sunshine and reeling seabirds”

I turn my back on the world of man and move into Svalbard’s mountainous interior, where I don’t meet another soul for a week. The next four days are slow, through Adventdalen along the corridors of cloudy rivers that are born of the glaciers that litter the mountains around me. At this latitude even humble 700-metre peaks sport them. Then it’s up into the relative heights of Reindalpasset. Hard going here, glaciers are at work and I plough through the debris of their industry. A day later I descend into the expanse of Reindalen, a green corridor through the mountains and ice punctuated by a line of nunatuks.

A windy first camp

© Mark Waring

Grey glacial water

© Mark Waring

Walking is tough on the detritus of glaciers. Camp is a nightly relief though it’s labour- intensive setting the fence. I delight in the shelter of my tarp and marvel at this place around me. It’s raw, elemental, enchanting and somewhat intimidating. I’m quite alone. Sleep is always welcome but I feel I’m surrendering myself to total vulnerability. The rifle lies close, cocked with the safety on. I anticipate fretfully the intensity and violence of a bear in camp. One night as I’m slipping into sleep, a sudden noise and flash of movement jolts me awake. I grab the rifle and aim; before me a startled reindeer stands at the perimeter of the fence. My pulse begins to slow as he skittles off.

Wildlife is a highlight of those days walking through Reindalen. The overhang of backpacking in polar bear country is offset by the company of wild reindeer, Arctic bird life and my first ever sighting of the rare Arctic fox. Years hiking the sub-Arctic and I’ve failed to spot ‘fjällräven’. Here though I spy two sets of vixens and cubs on consecutive days, a delight!

Coastal currents

After a week I tumble out of the mountains and approach the coast. Ahead lies Grönfjord and puffs of dark smoke signal Barentsburg. An incongruous experience as I approach its limits, grimy industry everywhere. I dodge decades- old heavy Soviet trucks loaded with coal as I pass through the heart of a working coal mine. Signs in Cyrillic usher me into the living heart of this Russian town of 600 souls. I turn left at a bust of a grim-faced Lenin and pass murals celebrating Soviet conquest over the Arctic, fading now after decades of hard winters.

Barentsburg is eccentric and the antithesis of smart Scandinavian Longyearbyen, but I love it. A mix of bright modern buildings and decaying Soviet brutalism, it’s a home nonetheless to workers and their families in the High Arctic. I wander its streets entranced at this living community framed by wilderness before Russian food and vodka wash away the aches of hard walking. Next morning I’m on the move again, following pockmarked streets past folksy wooden dachas and vast slabs of accommodation blocks. Heroic murals again, testament to the advance of Soviet science, are challenged by rusting machinery. Scenes from Russian folktales, painted bright on a school building, stand shoulder to shoulder with cosmonauts. Next I pass sheds of livestock which supplement the twice-yearly supply ship from southerly Archangel and then, drawing the bolt on the rifle, I’m out into the wilderness again.

Crumbling Barentsburg

© Mark Waring

The smell of Barentsburg lingers as I move north along the coastline. Camp that night is by the icy water of Isfjorden and I’m lulled to sleep by the lapping of the Barents Sea. An old trapper’s cabin proves an interesting detour next morning but that’s surpassed by my arrival at Coles Bay. Eight or so buildings before me were part of a former Russian coal mine abandoned in days in 1965. I explore and bunkhouses echo to the sound of my footsteps. The past hangs heavy. Newspapers in Russian from the early 1960s stacked neatly in cupboards. A table set for dinner in a crumbling kitchen. A bedroom with a neat bed and a fading photo of a smiling family pinned to the wall. Another uneconomic mine petrified in the era of the Sputnik.

Barentsburg needs heavy subsidy too but it’s the final statement of Russian intent in this key part of the Arctic. Down one final lonely corridor I go, 20 bedrooms deep, until I emerge blinking into bright sunshine and reeling seabirds. Past a tumbledown dock complete with scuttled barge and then it’s up into the hills to camp.

Next morning is a final push across the mountains that ring Longyearbyen, not an easy day. Loose rock and scree are everywhere, I tumble into gullies and sweat hard contouring Plateauberget until at last I’m standing above Longyearbyen. Below me cliffs sweep away, mine workings hanging on precariously. I thread my way down on a rough path, ten days backpacking coming to an end and I can drop my guard at last. I pause at the town’s graveyard. Famously, the last bodies were buried here in the 1920s. The Governor insists that dying is done off Svalbard, the decomposition of bodies being impossible in permafrost.

I allow myself a wry smile; I’ve learnt in the last ten days that Svalbard is full of ghosts. In abandoned mines, trappers’ huts and whaling stations, fast in the cold Arctic air the past echoes loud. This place is exceptional, and so are the steps you take to travel through it.

Check out Mark’s blog at One Swedish Summer.