The Cape Wrath Trail is among the UK’s toughest but also most rewarding long-distance routes – where better to find solitude and a break from the noise of switched-on modern living?

This feature was first published in the May 2019 issue of The Great Outdoors, and is part of our Cape Wrath Trail section. It has been published in partnership with our friends at SPOT.

By Alex Roddie

There’s a numb feeling in the back of my mind when I’ve spent a bit too long on Instagram, scrolling through a never- ending slideshow of gorgeous mountain views. I contribute to Instagram myself – as I do with several social media sites. But recently I’d started to wonder what the point of it all was. And I’d begun to resent the time and attention that these websites were stealing from me. Was it contributing to the anxiety that had crept up on me over the last few years? Something was wrong, but I didn’t know what. So I did what any #adventurer would do: I set myself a challenge.

Regular readers of this magazine may remember that a few years ago, The Great Outdoors published a feature I wrote about walking the Cape Wrath Trail. Back then, I described this journey up the west coast of Scotland as the “best, toughest, wildest, and most moving thing I’ve ever done”. Now I would be going back. But this time I wanted to complete the Cape Wrath Trail in winter – and, to help me make sense of my unease and anxiety, I’d do it without accessing the internet along the way.

The lack of a web connection might not seem a big deal to dyed-in-the-wool long-distance walkers; until recently, no one even had the option to take the internet backpacking. But there’s little phone signal along the Cape Wrath Trail, and the last time I’d been offline for more than a few days I was about 17 years old.

I would carry a SPOT X satellite communicator – which would enable me to send messages home to confirm I was ok, and also to call for emergency help in case of a crisis – but my mobile phone would remain at the bottom of my pack. I was looking forward to finding some real silence – whatever that means in 2019.

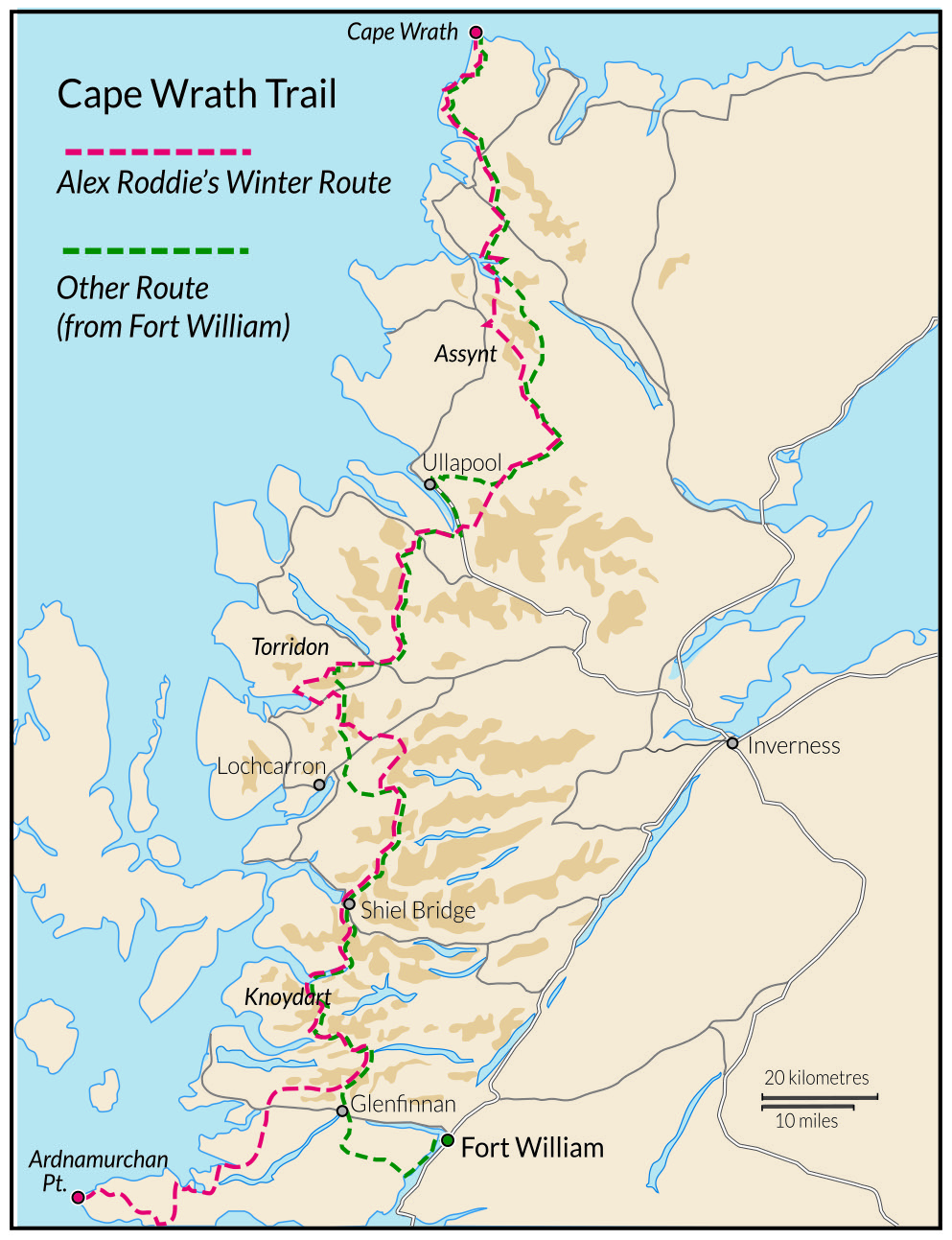

Alex’s route

Alex’s route

- Distance: 480km/299 miles

- Start: Ardnamurchan Point (the standard Cape Wrath Trail begins at Fort William)

- Finish: Cape Wrath lighthouse

- Transport: Access Ardnamurchan from Oban (ferry to Craignure, bus to Tobermory, then ferry to Kilchoan). At the end of the trail, a minibus connects with a ferry to the Durness side in summer; in winter a lengthy walk-out is required

- Maps: Harvey Cape Wrath Trail maps (South and North). Ardnamurchan is covered by OS Landranger 47 (Tobermory & North Mull) and Landranger 40 (Mallaig & Glenfinnan)

- Guidebook: Walking the Cape Wrath Trail, Iain Harper (Cicerone Press)

A false start

The plan had been to hike through Ardnamurchan before joining the Cape Wrath Trail at Glenfinnan. When I reached the Ardnamurchan lighthouse on a storm-lashed day in early February, and stood on the slick rock of the foreshore while shielding myself from the full force of the Atlantic blast, it felt far from the journey I’d imagined. I wanted snow and mountains. The forecast (which my brother James was texting to my SPOT X daily) promised nothing but storms.

The Ardnamurchan stage was tough. Insane winds drove me down from the high ground. As I staggered along paths turned to rivers by 32 hours of rain and sleet, cursing every kilo in my abominably heavy pack, I thought I’d give myself a break by doing a bit of road walking. Then, on a flat road at sea level, a gust blew me off my feet. I ended up in a B&B in Salen wondering what the hell I was doing. I had a faulty tent, all my gear was soaked, and I regretted every choice that had led me to that moment.

With calmer weather and a bothy roof over my head, Glenfinnan offered the chance to reset. At last I found a little real winter on the mountains edging Knoydart, which I explored while I waited for James to join up with me. My enthusiasm recovered.

Unusually, I was the oldest person in the bothy that night. I’d just settled down in front of the fire with new friends Mike and Louis, each of us enjoying a dram, when the door opened and a lean figure stepped through. He switched off his headlamp and stood there for a moment looking a little dazed, as if only just realising his fatigue.

“I might hike on to the next bothy,” he said when I asked him if he’d be staying, but in the end the temptation of fire and rest was too great. The young man called himself Skye. He was 16 years old and hiking Land’s End to John O’Groats via the CWT. Later, after he’d picked my brains about the trail, Skye mentioned that he was filming his trip but didn’t know what to do with the footage: “I’ve never had a social media account.” Half joking, I told him he wasn’t missing much.

On a dull, mild morning I met up with my brother and we trekked together into Knoydart – but not before I swapped my faulty tent for the spare he’d brought with him. At last I’d be able to camp without risking getting all my kit drenched again. “You could probably give me your snowshoes too,” James said, eyeing my colossal pack. “Winter’s gone for the time being.”

“This is one of the best sections of the trail, where pathless and rough miles follow a contour over heather and moraine through some of Scotland’s finest wild land”

I’d needed crampons and axe the previous day, but now the mountains were alive with meltwater cascades. I started to worry about the Knoydart river crossings. Even in summer, this section of the Cape Wrath Trail is an early test of competence. The Carnoch River had a missing bridge, and I’d planned a high-level detour over the Bealach Coire nan Gall to avoid it, but when we discussed our options James pointed out that the steep north side of the bealach probably concealed a thawing snow slope. Which did I fancy: a potentially dangerous bealach followed by two river crossings, or two different river crossings but no high ground?

Only the first crossing on the way to Glen Pean was serious enough to make us wary. I didn’t know whether the usual crossing further down would be safe. James pointed – he’d seen camo-clad estate workers on the far bank gesturing for us to cross immediately. It took us a couple of attempts to find a safe place, and after we made it to the other side I felt a weight lift from my mind.

James could only join me for a couple of days. He turned back a few miles after we left A’ Chuil bothy. This was the fork in the road, the place to make the call: up and over the bealach to avoid the missing bridge, or towards the Carnoch to avoid dodgy snow up high? I chose the Carnoch route. “Good decision,” James said before retracing his steps back towards Glenfinnan. And my luck held. When I reached the Carnoch, it was an easy crossing in the conditions. It could have been a lot worse.

An early spring

Winter had long gone by the time I met up with TGO’s Chris Townsend in Torridon. Chris led the way around the back of Liathach, where we resumed the Cape Wrath Trail on the path up to Coire Mhic Fhearchair. This is one of the best sections of the trail, where pathless and rough miles follow a contour over heather and moraine through some of Scotland’s finest wild land.

As we hiked, Chris and I chatted about my no-internet experiment. We explored the idea that commentators who take a hardline stance on the mental health impact of social media fail to acknowledge the good it can do. I’d been offline for two weeks and readily accepted this viewpoint. I could feel my own cynicism evaporating with every mile I walked, every stranger I spoke to in person instead of through Twitter. But the truth is that I thought about my online life seldom. When Chris and I set up camp at a sheltered spot beneath Beinn Eighe, the notion of looking for an Instagrammable pitch couldn’t have been further from my mind.

After I left Chris and continued north, the calendar said it was winter, as did my heavy pack and big boots, but everything else screamed summer. The winds dropped, rain became a distant memory, and I found myself hiking in shirtsleeves. I started to see frogs spawning in puddles and even the odd lizard. My mileage increased too.

I kept bumping into Skye, the 16-year- old LEJOGer I’d first met at Glenfinnan. We walked together for a few hours in Assynt. As we chatted, I found myself awed by his drive and determination, and impressed by his knowledge of environmental issues and interest in rewilding. He was self-funding his big walk with online businesses and had a big wish- list of international long-distance hikes. After seeing how well he was doing on the Cape Wrath Trail, I had no doubt he could achieve his goals. Walking with Skye made me feel positive about the future – here was a 16-year-old who knew and cared about the environment of the Highlands, and wanted to find a way to use his big walk to make a difference.

“As I stood there on that farthest shore, confronted by a jarring example of ecological breakdown, I realised that my worries about the internet were laughably trivial”

However, my optimism was soon tested – three days before the end of my Cape Wrath Trail, on the evening that hundreds of ticks invaded my tent. I’d camped in a field with evidence of heavy deer presence nearby. By the time I realised my error, after seeing ticks on my clothing, stuffsacks, and flysheet, I couldn’t be bothered to move camp so made ready to repel boarders. At this point on the trail, I was using a lightweight Mountain Laurel Designs Duomid tarp with a basic groundsheet and bivvy bag, but no inner. The only way I could put something between me and the ticks was to seal myself in the bivvy bag and worry about the rest of my gear later. I stopped counting at 50 ticks, but there must have been hundreds, and the next morning I evicted many more from my rucksack and boots.

As I set out again, I realised that the presence of so many ticks in February – usually the peak of winter – was yet one more sign of something deeply and fundamentally broken.

A shifting baseline

Sandwood Bay guards a remote and beautiful beach about 12 miles from the Cape Wrath lighthouse and the end of the trail. I walked across the dunes in late afternoon as the light was starting to soften. Behind me, the sea stack of Am Buachaille drew the eye, tempting me to anthropomorphise it as a sentinel welcoming pilgrims. The silence and solitude were magnificent. I wondered if I’d remember what this felt like after I’d returned home and plugged myself back in to the noise of the web.

Then I saw something I couldn’t identify a mile along the beach. A standing stone? Junk left by the tide? As I approached, the shape revealed itself as a colossal skull, rooted there in the sand like a relic of some primordial creature. I stood before it electrified with awe. The skull was well over a metre long and my mind grappled with words like ‘dinosaur’ and ‘dragon’ before settling on ‘whale’. And that’s when it really hit me. As I stood there on that farthest shore, confronted by a jarring example of ecological breakdown, I realised that my worries about the internet were laughably trivial.

While I had been fretting about whether social media was ruining my ability to concentrate, dozens of creatures like this one – which I later identified as an endangered Northern Bottlenose Whale – were being beached on Scottish shores. Nobody knows for sure what is causing this tragedy, but most theories point at us. This is just one story in a vast ecological crisis.

I’m not the first person to be shocked by immediate and tangible evidence of climate change and biodiversity loss, and I certainly won’t be the last. But as I leafed through the bothy book at Strathchailleach and saw a sketch of the rotting whale carcass on the beach, as I squinted through the window at the silent and treeless landscape outside, I couldn’t shake my discomfort. Baselines shift but our perception of these changes is important.

What about my offline experiment? By the end of the trail it hardly seemed to matter. I didn’t miss the internet, but I’d made my peace with it, and I’d come to realise that my anxiety couldn’t be entirely blamed upon the web.

Going offline for a month cured me of my cynicism regarding social media and made me more appreciative for the good it can do, especially in environmental campaigning. Real changes can be made this way. So share petitions, raise awareness, and don’t feel too bad about Instagramming your wild camps – but it’s also worth disconnecting completely from time to time, and not just for a couple of days. Genuine silence is rare and special in our hyper-connected era. You might discover something about yourself and the world around you if you take the time to listen.

The Cape Wrath Trail

The Cape Wrath Trail is one of the most serious long-distance walks in the country and also one of the most stunning, passing through mile after mile of magnificent mountain landscapes, including parts of Knoydart, Torridon and Assynt.

This informal route, often pathless over rugged terrain, extends from Fort William to Cape Wrath with numerous possible variations. A typical Cape Wrath Trail walk will be roughly 230–250 miles in length.

When planning my winter CWT, I decided to create an extended route beginning at Ardnamurchan Point. This would allow me to explore Ardnamurchan and Moidart before joining the Knoydart variant of the standard Cape Wrath Trail at Glenfinnan.

I also plotted several options taking in Munro summits and major ridges along the way, and planned to take these variants if I encountered fine, stable winter weather. Such conditions did not materialise, and the only Munros I succeeded in climbing were Sgurr nan Coireachan and Sgurr Thuilm above Glenfinnan just before the big thaw hit. After Glenfinnan I kept to a fairly standard Cape Wrath Trail line.

Return to the Cape Wrath Trail home page

Header image © James Roddie Photography