Andrew Galloway explores the mining history of North Wales, and makes some unexpected discoveries

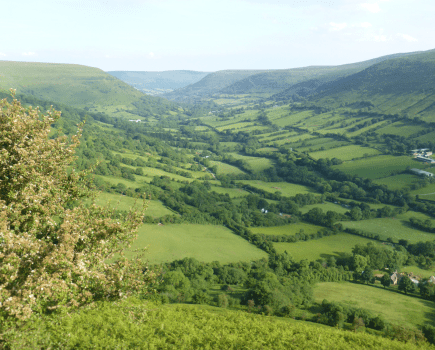

A track from the village led north towards the limb of Croesor Bach. So named by sailors entering Porthmadog due to its apparent similarity to a knight’s helmet, Cnicht stood like a sentinel above Cwm Croesor. The climb to the summit was arduous, and from here the contours plunged sharply into the valley floor, offering a vertiginous view of Croesor Quarry, perched at over 500 metres on the northern slopes of Moelwyn Mawr, and far below, the disused path of the Croesor tramway, which once hauled slate from the head of the valley to waiting ships moored at Porthmadog.

To the north-west lay the panorama of the Snowdonia massif, Yr Wyddfa itself resembling the head of an angular sphinx, Bwlch Main the backbone and tail, Bwlch y Saethau the couchant paws, stretched out beneath a sky as blue as an Egyptian water lily. I followed the broad ridge north-east from the summit to Llyn yr Adar. From the head of the lake a track contoured around Cwm Corisiog, heading south to the disused quarries of Rhosydd, the silent, desolate Machu Picchu of the Welsh Hills.

Quarrying at Rhosydd began in the 1830s. By 1883 the quarry was producing four to five thousand tonnes of slate per year and employed 200 men. The slate was extracted from underground, the discarded waste slag still forming immense lobes of fractured rock fanning out from the ruined buildings like fat fingers. Much of the quarry machinery was stripped away following the closure, although it is amazing what has survived in this remote place: the rusted gearbox of a vehicle, perhaps a trolley-car from the tramway, ‘megryn’ wheels from carts used to transport materials from the heart of the mountain, tall slate-stone fences, built because slate was cheaper and more readily available than wood, standing still, despite a hundred years of thunderous winds and blistering cold. Many of the adits (shafts) at Rhosydd leading to the giant slate caverns are still open, but it is advisable not to enter them without the assistance of an experienced guide. Roof collapse and rock-fall are common.

I climbed the steep incline from the rear of the old quarry barracks towards the open moorland, careful to avoid the many open shafts and unmarked workings, until I reached the eastern limb of Moelwyn Mawr, high above the Llyn Stwlan reservoir that feeds water to the hydro-electric station at Tanygrisiau.

Although the narrow ridge leading west from the summit of Moelwyn Mawr looks tempting, the ground beyond drops very steeply and is best left for the more experienced. I decided instead to head south into Bwlch Stwlan then up to Moelwyn Bach, thus avoiding a potentially dangerous descent while also bagging the smaller of the Moelwyn peaks. The western limb of the little Moelwyn led me downslope past many more abandoned workings, towards Penrallt, then back to Croesor.

As I was passing the Oriel Caffi, there was still some activity inside so I popped in for a quick mochachino and a wander around the gallery. A black and white photograph of the silky Afon Croesor in the mist caught my attention. I decided to indulge and asked the lady serving the coffee if I could buy it. She asked me to wait a moment while she called the photographer. Mr Ben-like he appeared in the café, brandishing volumes of his work. We spent the next hour or more sitting by the fire, browsing through his photographs, me trying to impress him with the few words of Welsh I know, him telling me stories of his work, of the valley, and of the quarries and mines of Rhosydd.

ROUTE DESCRIPTION

- From the car park at Croesor, follow the fingerpost indicating Cnicht, then take the path to the NE that leads onto the limb of Croesor Bach. Continue along the ridge until the cone-shaped summit of Cnicht is reached. Carefully ascend the zig-zag path that crosses the scree.

- From the summit continue NE following the gentler ridge until it merges with open moorland at Llyn yr Adar.

- From the NE side of the lake, follow the track to the SE that meanders through Llynau Diffwys, eventually leading to the disused quarries at Rhosydd.

- Climb the steep incline to the rear of the ruined barracks at Rhosydd, heading S for approx. 1km, carefully avoiding open quarry workings, then pick up the track that ascends the eastern limb of Moelwyn Mawr, becoming steep towards the summit.

- Retrace your steps briefly – approx 100m – to the break of slope and descend the steep southern limb of Moelwyn Mawr into the col, then climb, still south, to the summit of Moelwyn Bach. From here follow the western limb, past more disused workings to the wood at Penrallt, there taking the road for 1km to return to Croesor.

Andrew Galloway explores the mining history of North Wales, and makes some unexpected discoveries

A track from the village led north towards the limb of Croesor Bach. So named by sailors entering Porthmadog due to its apparent similarity to a knight’s helmet, Cnicht stood like a sentinel above Cwm Croesor. The climb to the summit was arduous, and from here the contours plunged sharply into the valley floor, offering a vertiginous view of Croesor Quarry, perched at over 500 metres on the northern slopes of Moelwyn Mawr, and far below, the disused path of the Croesor tramway, which once hauled slate from the head of the valley to waiting ships moored at Porthmadog.

To the north-west lay the panorama of the Snowdonia massif, Yr Wyddfa itself resembling the head of an angular sphinx, Bwlch Main the backbone and tail, Bwlch y Saethau the couchant paws, stretched out beneath a sky as blue as an Egyptian water lily. I followed the broad ridge north-east from the summit to Llyn yr Adar. From the head of the lake a track contoured around Cwm Corisiog, heading south to the disused quarries of Rhosydd, the silent, desolate Machu Picchu of the Welsh Hills.

Quarrying at Rhosydd began in the 1830s. By 1883 the quarry was producing four to five thousand tonnes of slate per year and employed 200 men. The slate was extracted from underground, the discarded waste slag still forming immense lobes of fractured rock fanning out from the ruined buildings like fat fingers. Much of the quarry machinery was stripped away following the closure, although it is amazing what has survived in this remote place: the rusted gearbox of a vehicle, perhaps a trolley-car from the tramway, ‘megryn’ wheels from carts used to transport materials from the heart of the mountain, tall slate-stone fences, built because slate was cheaper and more readily available than wood, standing still, despite a hundred years of thunderous winds and blistering cold. Many of the adits (shafts) at Rhosydd leading to the giant slate caverns are still open, but it is advisable not to enter them without the assistance of an experienced guide. Roof collapse and rock-fall are common.

I climbed the steep incline from the rear of the old quarry barracks towards the open moorland, careful to avoid the many open shafts and unmarked workings, until I reached the eastern limb of Moelwyn Mawr, high above the Llyn Stwlan reservoir that feeds water to the hydro-electric station at Tanygrisiau.

Although the narrow ridge leading west from the summit of Moelwyn Mawr looks tempting, the ground beyond drops very steeply and is best left for the more experienced. I decided instead to head south into Bwlch Stwlan then up to Moelwyn Bach, thus avoiding a potentially dangerous descent while also bagging the smaller of the Moelwyn peaks. The western limb of the little Moelwyn led me downslope past many more abandoned workings, towards Penrallt, then back to Croesor.

As I was passing the Oriel Caffi, there was still some activity inside so I popped in for a quick mochachino and a wander around the gallery. A black and white photograph of the silky Afon Croesor in the mist caught my attention. I decided to indulge and asked the lady serving the coffee if I could buy it. She asked me to wait a moment while she called the photographer. Mr Ben-like he appeared in the café, brandishing volumes of his work. We spent the next hour or more sitting by the fire, browsing through his photographs, me trying to impress him with the few words of Welsh I know, him telling me stories of his work, of the valley, and of the quarries and mines of Rhosydd.

ROUTE DESCRIPTION

- From the car park at Croesor, follow the fingerpost indicating Cnicht, then take the path to the NE that leads onto the limb of Croesor Bach. Continue along the ridge until the cone-shaped summit of Cnicht is reached. Carefully ascend the zig-zag path that crosses the scree.

- From the summit continue NE following the gentler ridge until it merges with open moorland at Llyn yr Adar.

- From the NE side of the lake, follow the track to the SE that meanders through Llynau Diffwys, eventually leading to the disused quarries at Rhosydd.

- Climb the steep incline to the rear of the ruined barracks at Rhosydd, heading S for approx. 1km, carefully avoiding open quarry workings, then pick up the track that ascends the eastern limb of Moelwyn Mawr, becoming steep towards the summit.

- Retrace your steps briefly – approx 100m – to the break of slope and descend the steep southern limb of Moelwyn Mawr into the col, then climb, still south, to the summit of Moelwyn Bach. From here follow the western limb, past more disused workings to the wood at Penrallt, there taking the road for 1km to return to Croesor.