In case you haven’t already heard, the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales National Parks have both been extended to take on substantial chunks of land between them. Here Jon Sparks explores these landscapes with new protection on a three-day walk

A wall runs over Middleton Fell, reaching the ridge a short way south-west of the summit (Calf Top) and following the high ground for around 5km. For nearly all this distance, it also forms the boundary of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Since 1954, the steep slopes east of this wall, dropping into Barbondale and Dentdale, have been in the Park. Th e sprawling moorland west of the wall, falling more gradually to the Lune valley, has not.

This will soon change. On 23 October 2015, Environment Secretary Liz Truss announced that plans to extend the Dales and Lake District National Parks would take effect from August 2016. These plans have had a long gestation: official consultation began in 2009 and a public enquiry reported favourably in mid-2013. It will add just 3% to the area of the Lake District National Park, but 24% to the Yorkshire Dales. And for the first time two UK National Parks will actually meet, with a common boundary in the Lune Gorge.

Well, almost: a narrow corridor remains along the M6 and West Coast Main Line. You won’t be able to step from Dales to Lakes in a single stride, but it will take barely five minutes’ walking. I’d been toying with the idea of a continuous walk through the areas concerned. I already knew most of them, but was keen to link it all together.

The announcement of the extensions gave me the nudge I needed but, by the time I could snatch three clear days it was mid-November. A brilliant autumn had turned tempestuous. Even the squabbling schoolkids on the Lancaster to Kirkby Lonsdale bus were impressed by the flooded fields of the Lune valley. I would have liked to start my walk in the gorgeous valley of Leck Beck, at the southernmost end of the Dales extension, with its secretive limestone gorge, Easegill Kirk. But the clocks had gone back, time was tight, and the following stretch, over Middleton Fell, was unknown territory and I wanted to prioritise the areas I knew least.

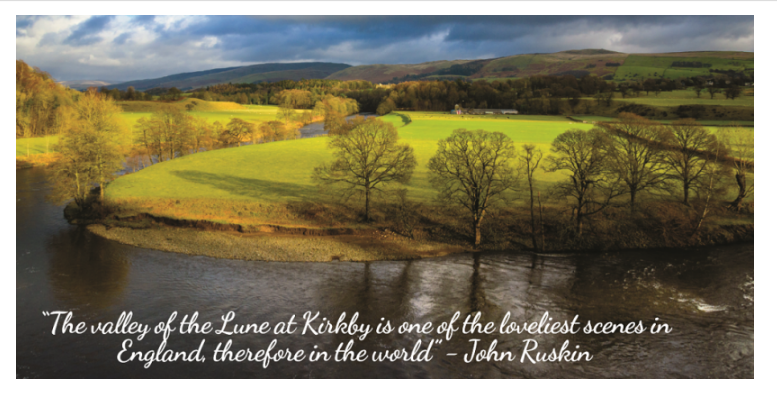

For the same reasons, I also missed out Ruskin’s View. This perch below Kirkby Lonsdale churchyard looks over a loop of the River Lune, towards the fells. The view was painted by Turner long before John Ruskin’s visit in 1875. Ruskin wrote: “The valley of the Lune at Kirkby is one of the loveliest scenes in England, therefore in the world. I do not know in all my country, still less in France or Italy, a place more naturally divine.”

I recalled previous visits to the View as I headed out of town, across the medieval Devil’s Bridge and up narrow lanes to Casterton’s Fell Road. In an hour on the Fell Road, I saw one car, one outdoor education minibus and one quad bike with a sheepdog perched behind the driver.

Omitting Leck Beck was a wrench, but I had good view over it from the lonely road. Tarmac ended by Bullpot Farm, a cavers’ centre. A rougher track curved left and down into Barbondale. I scanned the facing slope, vainly seeking a weakness. This climb onto Middleton Fell had concerned me since I started planning the route. In the end it was simple enough, just brutally steep for 200 vertical metres. After 25 minutes of not-fun, the slope eased, though it all got a bit vague. I couldn’t definitely say I was on the ridge until I was approaching the large cairn on Castle Knott.

The wet-looking dip in the ridge before the climb to Calf Top also had a bark worse than its bite. However, the wind was picking up, and looking back I saw veils of rain heading my way. At the shoulder before the summit, I huddled in the lee of the boundary wall, a metre inside the existing National Park, to scramble into extra layers before devouring sandwiches. The rain whipped away overhead as I ate, and big splashes of sun cruised the fells as I moved on. The summit trig point, like the sketchy path, lies just outside the National Park.

Down to my right, Dentdale lounged luscious and green, but to the left, the Lune valley looked equally enticing. At first glance, at least, it’s not suffered massively by its decades of exclusion from the National Park. I recalled a footnote to the story of Ruskin’s View. The farmer of Kirfit Hall – bang in the centre of the view – took umbrage when refused planning permission to convert a barn into holiday cottages, and repainted it in bold multicoloured stripes.

This ‘Liquorice Allsort’ offends some, amuses others; I think I lean to amused. What puzzled me was why I’d never climbed Middleton Fell before. It’s respectably high (610m; a more memorable 1999ft on some old maps), extensive, and prominent too, forming much of the backdrop to Ruskin’s View. Yet somehow it not only got left out of the National Park; Wainwright spurned it too, leaving a gap between Walks in Limestone Country and Walks on the Howgill Fells.

To my relief, the going underfoot was generally good. However, as the descending ridge curved round northwestward, progress became laborious, as the wind rose to a full gale. Still, I was lucky, as showers, though frequent, kept missing me. Often they’d slide through the gap between Middleton Fell and the Howgills. At times, a rainbow neatly filled the ‘V’ of the Lune Gorge, where the Park extensions (almost) meet.

Words and pictures: Jon Sparks