Few backpacking routes offer such varied rewards as this week-long walk through the Winged Isle

Words by Alex Roddie / Images by James Roddie Photography

This feature was first published in the October 2016 print issue of this magazine.

You have a week off work. You want to go backpacking, and you want to experience the best that Scotland can offer: mountains, sea, coastline, wildlife, and history. Where do you go? I think the answer is simple. It’s Skye.

When my brother James and I started planning our hike of the Skye Trail, we had few expectations. We knew that the trail weaves a complex route around the coastline and through the mountainous heartland before traversing the fabled Trotternish Ridge. We knew that, like all the best trails, there are several variants and no signposts. And – perhaps most of all – we knew that the weather on Skye is notoriously dreadful, and that we’d probably spend the week plodding along in mist and rain, wishing we’d stayed in the pub.

I was expecting a bit of exercise in the hills for a few days, but I hadn’t prepared myself to fall in love with Skye all over again.

‘Wow, look at this! Another ruin. And there’s a standing stone down there.’

I heard James’s call from some distance away. I’d crawled under the archway of a decaying house, part of the abandoned settlement at Boreraig. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine men driving cattle through here, a woman sitting outside her house weaving, perhaps children running along what must once have been a street. Now bracken and cotton grass grew tall where people once lived.

The standing stone marked a point of departure. Behind us lay Broadford, shops, people, our lives and jobs; ahead of us lay a journey into other worlds and realities.

Our first experience of Skye’s coastline was honest and rough with few hints of beauty. A wedge of cliffs plunged down through vegetation and bands of shattered rock to the edge of Loch Eishort. We followed a path up and down, always staying above the high-tide mark where washed-up fragments of multicoloured plastic looked like so many discarded Christmas decorations.

The Highland Clearances

Against a backdrop of major social and agricultural change in the 18th century, landowners throughout the Highlands began to clear their land of impoverished tenants to make room for more profitable sheep farming. Thousands of people were forced from their homes and many died in the process. On Skye it is impossible to ignore this dark episode of Scottish history; its legacy is everywhere. Abandoned settlements are found throughout the island and many areas have never been repopulated. The Skye Trail passes the abandoned village of Boreraig – an eerie and sad place, where in 1852 the community was removed by force and their houses burnt.

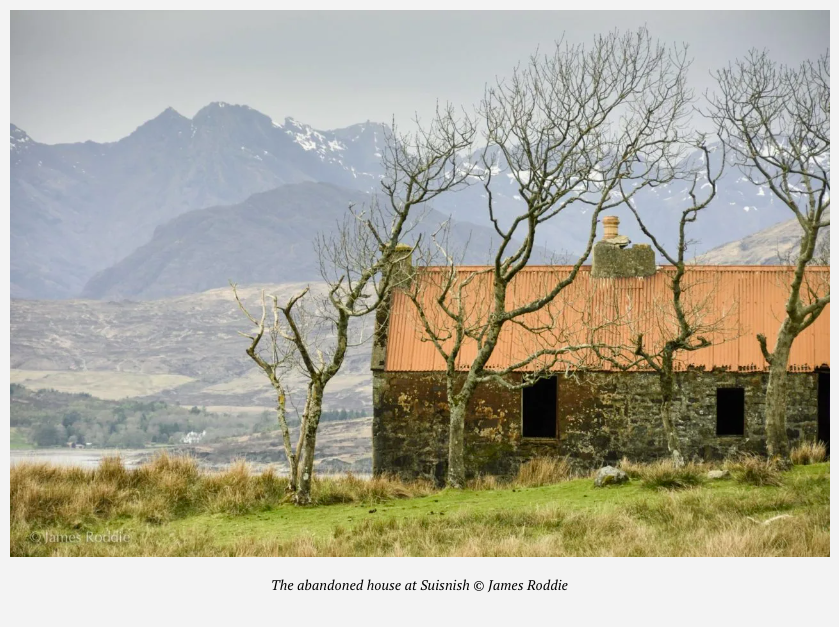

Later, at Suisnish, we discovered an abandoned farmhouse surrounded by trees bent low by the prevailing winds. Inside were the rusted remains of an old bed frame and the corpse of a long-dead lamb.

We camped at the head of Loch Slapin, having followed the coastline for most of the day, watching its moods change with the gusting winds and rain showers that swept in from the Atlantic. Bla Bheinn’s reptilian prow served as a constant reminder that soon we’d leave the coast and enter the mountains.

Underground scrambling

James is a caver. I’m not. When he told me about the Spar Cave and said that it was easily accessible from the trail, I took his words at face value. The reality is a lot more adventurous – and a lot more fun.

We jumped over a stile and descended to a gully that led to a geo at the edge of the water. Timing’s critical here; only at low tide is access to the Spar Cave possible on foot. James led the way over boulders until we could see the entrance of a chasm that looked a bit like a set from The Lord of the Rings.

Even when we stood at the entrance of the cave – a towering, narrow slot, dripping with slime – I had no idea what was to come. I expected a level walk to emerge at some kind of chamber. But when we stepped into the cold darkness and switched on our head torches, I found myself face to face with a wall of flowstone slanting up at a steep angle.

‘So this is as far as we go?’ I asked. ’Nope. We climb up here,’ James said.

The Spar Cave

The Highlands aren’t often associated with caving and potholing, but Skye hosts dozens of caves ranging from tiny caverns to major stream-caves hundreds of metres long. Whilst many are only accessible to experienced cavers the Spar Cave near Elgol offers adventurous walkers an opportunity to get a taste of Skye’s subterranean wonders. This surprising and beautiful place is only a short diversion from the Skye Trail. It’s only accessible at low tide so good timing is essential, as is a head torch and some scrambling ability. Instructions for finding the cave can be found in Skye Scrambles (Scottish Mountaineering Club).

Easily accessible by the standards of a caver, I now learned, actually meant underground Grade 1 scrambling up a flowstone waterfall. But it was easier than it looked. The rock was actually very grippy, and the scramble was more like a 45˚ staircase than a real climb. At the top, we found ourselves in a crystalline chamber of amazing beauty, draped with stalactites. It felt as far from the Skye Trail above as the trail itself felt from everyday life, and I can’t imagine a more unique moment on any long-distance footpath in the UK.

Over the Bad Step

Coastline blended into mountains on the day when we left Camasunary bothy and began the hike to Coruisk.

We’d heard warnings about the path around the edge of Sgurr na Stri: incredibly rough, difficult to follow, time consuming, and with one obstacle fearsome enough to be called the Bad Step. I thought it sounded brilliant. When we crossed the river, the sun was already high in the sky and kicking out real heat. It wasn’t a day for hurrying. James lingered to take photos and I often squinted into the dazzling brightness, hopeful of spotting an otter amongst the seaweed below. Sadly, I saw yet more plastic.

We got lucky when the path veered north towards the inlet. A motorboat cut ripples through the still blue waters, but it didn’t disturb the wildlife on an island just off the coast. James pointed out seals sunning themselves on the rocks, and then – splash! – an otter slipped below the surface before coming up again and bobbling along in the current.

After overcoming exposed but straightforward scrambling moves on the Bad Step, we entered the hidden bowl of Coruisk. The heat was now so oppressive that we crashed on the banks of the river for a while. The motorboat had disgorged its cargo of passengers onto the beach, and now families scampered all over the rocks about us, the children paddling in the water and skipping stones. I often prefer to be alone in the mountains, but this time it felt right that other people should be here enjoying this incredible place. Those children will go home and remember their sunny afternoon in Coruisk. Perhaps they will grow up to be adults with an active interest in protecting the wild places they have enjoyed.

We felt a little wilted as we climbed up out of Coruisk towards Glen Sligachan. Fierce heat was taking its toll, but we stopped at every stream to filter water and keep ourselves hydrated. Glen Sligachan, when we beheld it, looked like another world: an arid defile surrounded by peaks more sublime than beautiful, all craggy spires and unfriendly flanks. It would be a dramatic place in a snowstorm, I thought, perhaps craving winter’s chill as I lathered on more sunscreen.

Sligachan was just the pitstop we needed after a thirsty day. After beer and venison casserole, we got out the map and started planning the next stage of our journey.

Magical Trotternish

‘Do you reckon four litres each will be enough?’

I considered James’s question. It was the fourth day of unbroken sunshine and heat, and we were about to take on the Trotternish Ridge: the grand finale of the Skye Trail and a famous walk in its own right. It’s around 36km in length and takes in many summits, but the map indicated few water sources along the way. ‘Better make that five,’ I said.

Although James already knew most of the ridge well, it was my first time up amongst these hills. They aren’t Munros, so a few years ago when I was exploring Skye I hadn’t thought them worthy of my attention. Now, with a bit more experience and a more inclusive perspective on hillwalking, I couldn’t wait. When we stood on the summit of Ben Dearg, and looked north to the long chain of serrated tops sprawling for miles into the heat haze, I realised that this was was going to be a truly classic walk.

And it was. The Storr grabs all the headlines with its crazy spires, but we found more subtle rewards in the rhythm of up and down, bealach and summit, crest and gully. Eagles were our constant companions. Once, we saw the gnawed skull of a lamb perched on a rock at the edge, as if left in offering.

Wildlife

Skye is arguably the best place in Scotland to see golden eagles, with the highest density of nesting pairs found anywhere in the country. Otters are hard to spot but can be found along much of the coastline, along with many seals. There are good opportunities to see dolphins and whales from land; sightings are even possible from some hills. During the summer, boat trips can be taken to see white-tailed eagles, puffins, marine mammals and a wide variety of birdlife.

We camped right on the brim of the precipice. As the light faded and James photographed the sunset, I tugged at guylines and made the Trailstar secure against the ferocious updrafts from the cliff edge. It would have been more sheltered further back, but this was the place to be, suspended above the wonderland of crag where the eagles hunted. We cooked our evening meal and wrote in our journals conscious of that awesome vertical drop just a couple of feet from our heads. But it didn’t bother me. It felt right to be there.

That night, two distinct sounds melded into a symphony of wildness on that most special of summit camps. Gusts surged up the cliffs and over our heads – a strangely coherent and orchestrated sound, as if the roar of the wind had been formed into chords. Then, in the pauses of absolute silence, a ring ouzel called out over the wild crest of the ridge. I heard it in my dreams, and I heard it again when we woke in time to see the dawn fireball lighting up the mainland. An eagle flitted through the shadow and rays of golden light that painted the cliffs far beneath us.

When we finally stood at the northernmost tip of Skye, on the strange and beautiful peninsula of Rubha Hunish where waves crashed against the cliffs and sea birds screeched, we knew that we’d made the right choice hiking northbound. To begin here, and walk away from all this back towards ordinary things and real life, would feel wrong to me. But begin at Broadford and inestimable wonders lie ahead of you every single day right until the end.

The Skye Trail is not the longest, hardest, wildest, or most famous long-distance trail in Scotland. Most backpackers with a few Munros under their belt will be quite capable of hiking it, and we never had to really push ourselves (the most we walked in a day was fifteen miles). But I have never finished a week’s walking feeling so enriched. On Skye there is a sense that other worlds float just beneath the surface, and by hiking the Skye Trail you might be able to glimpse them.

Essential information

Total distance – 67 to 83 miles (109 to 134km) depending on exact route.

How many days – 6 or 7 days.

Guidebook – The Skye Trail, by Helen and Paul Webster, is published by Cicerone. Cameron McNeish, the former editor of this magazine and the creator of the Skye Trail, has published a book, The Skye Trail: A Journey through the Isle of Skye. An accompanying DVD is also available via www.stridingedge.com.

Map – Skye Trail (Harvey: http://www.harveymaps.co.uk/)

Accommodation – Plentiful wild camping opportunities throughout. Hotels and hostels can be found in Broadford, Sligachan, Portree and Flodigarry. There are campsites at Sligachan and Torvaig. The smaller villages of Elgol and Torrin have a number of B&Bs. A new bothy has recently opened at Camusunary, and ‘The Lookout’ bothy sleeps a small number of people at Rubha Hunish.

Travel – There are three ferry ports on Skye, serviced by Caledonian MacBrayne (www.calmac.co.uk). Citylink buses also travel to the island. More detail on travel to and within Skye is available from www.isleofskye.com.