The Fjällräven Classic is an annual 68-mile / 110km backpacking event in one of Europe’s most northerly wildernesses, the awe-inspiring mountain landscape of Swedish Lapland.

In our September 2018 issue, you’ll find our 35-page Scandinavia Outdoors supplement, which aims to demonstrate that Norway, Sweden and Finland can justifiably claim to be home to Europe’s best backpacking.

We’ve selected some features on Scandi backpacking from our archives, and over the coming weeks we’ll be republishing them online in full for the first time.

This feature was first published in the October 2012 issue of The Great Outdoors.

An Arctic Adventure by Carey Davies

Contents

- Fjälls and Fells

- The Kungsleden

- The Fjällräven Classic vs. the TGO Challenge

- Taking part in the Fjällräven Classic

A band is playing. Booze is flowing. People are dancing. I’ve just been grabbed by the legs, joisted on top of a waving forest of sweaty arms and carried above the small but seething crowd like a conquering hero, with a (miraculously unspilled) beer in hand, shouting a ballpark approximation of the words to something by Kings of Leon.

Somehow I’ve managed to find myself crowd-surfing, an act I haven’t indulged in since I was roughly 17 years of age and frequenting the less reputable musical establishments of Leeds. But this is not Leeds – this is an outsized tepee in a small village 120 miles inside the Arctic Circle, in Swedish Lapland, and it’s a strange way for a backpacking trip to end.

For the last five days I have been hiking through spectacular wilderness in the brooding presence of Sweden’s highest mountains, and along part of the mighty Kungsleden (‘King’s Trail’). I’ve been journeying through one of the most sparsely populated places in Europe, a 12-hour train ride away from the nearest ‘big’ city and a landscape which has remained much as it was at the end of the last Ice Age. But I haven’t been alone.

Far from it, in fact. The Fjällräven Classic is a 68-mile/110km organised backpacking event through some of the most awesome landscapes in Scandinavia. Participants are self-supported, carrying their own food and equipment and navigating themselves along the route, but that’s where the similarities with a conventional backpacking trip end. Walkers also have the benefit of a huge support and safety system provided by Fjällräven and a small army of volunteers. There are six checkpoints along the route, manned by 120 enthusiasts, who check in hikers, provide medical care or supplies, and even rustle up the odd reindeer kebab or lingonberry pancake. Food for the trail is provided, transport is laid on, and crews are on standby in case of emergency. It’s a wilderness backpack with a safety net, where much of the organisation is taken care of – and where you are likely to find yourself in the company of plenty of other people.

This year’s Fjällräven Classic attracted 2000 backpackers from 22 different countries. In previous years the event has had a competitive element, with participants being awarded gold, silver and bronze medals depending on their finishing time, but this was scrapped in 2012. In an egalitarian arrangement which would appal to David Cameron, everybody now gets gold. Some still choose to run it (the record time is around 13 hours) but there is no great hurry; entrants have as long as seven days to complete their journey. So the level of challenge is customisable – turn it into an ultra-run if you wish, but it’s also a great event for beginner backpackers or those who would otherwise be intimidated by the prospect of days alone in the Arctic backcountry.

The result is an event which feels less like a race and more like a festival, a folk celebration of Sweden’s wild north. There can’t be many other long-distance outdoor events with an age range spanning from one-and-a-half (admittedly possibly not a self-supported backpacker in the strict sense) to 76. In fact, its closest counterpart is probably our very own TGO Challenge (see below for a comparison of the two). Even if walking in such an organised event isn’t your cup of tea, there is no denying its ethos of inclusivity is quite remarkable. In fact, from my experience on the trip, the average age seemed mostly on the young side; a positive thing from the point of view of backpacking’s future.

Six days earlier, I had arrived in the town of Kiruna on a flight from Stockholm – a journey practically the length of Sweden, covering a distance which, if undertaken in a southerly direction, would end roughly in Rome. A gymnasium in the town of Kiruna had been commandeered by Fjällräven for the pre-hike preparations, where participants came to register for the trip, stock up on supplies and buy any last-minute gear they needed. It resembled a well-organised disaster relief effort, but with healthier-looking people. Clothing and equipment was piled in boxes and hanging from the walls. Hikers waited to register in lines then helped themselves to packages of dehydrated food.

The following day we travelled to the start of the trek in Nikkaluokta, a village of the indigenous Sami people. The Sami are the original inhabitants of the Sápmi region – a swathe of territory stretching across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia’s Kola Peninsula – and the trek passes through land which they have traditionally used for reindeer herding. Hundreds of backpackers stood in the morning sun, limbering up, queuing for the toilet or marinating themselves in sun cream and mosquito repellent. The orange flags participants are required to carry shone brightly from backpacks.

It was not your typical beginning to a backpacking trip (the drop-off on a lonely stretch of road by an incredulous bus driver, the request- only train stop at Nowherebridge…). This was more like the start of a marathon. The strains of a traditional Sami song drifted over the crowd (followed, for reasons that were harder to fathom, by the opening music to Star Wars). A countdown followed, and a vast herd of orange flags moved off in the direction of the mountains.

“And next to the burbling river which wound around the site was a sauna. Yes, a sauna. Never has a rudimentary bothy seemed quite so rudimentary”

The first few miles were a procession of orange (not of the banners-and-bowler-hats type, thankfully) as several hundred backpackers narrowed into a single path. Fjällräven separates the 2000 participants into groups and staggers the starts over two days, but they are still congested affairs initially. After only a few miles, however, the crowd began to thin out and break up as the people within it found their own pace. A hush settled, and we found ourselves walking through verdant forests of tangled mountain birch, past rocky ice-clear rivers, and through marshy meadows of long grass and white bog cotton.

In the distance, a line of peaks beckoned us forward. The range includes the glacier-topped Kebnekaise massif, at 2106m (6909ft) the highest mountain in Sweden. But the view as we drew closer was dominated by the arresting Tolpagorni (1662m/4542ft), a fang in a mouthful of molars cutting up with an angular ferocity that contrasted sharply with its rounded neighbours. Here, winter lasts for 200 days a year and, despite the fact we were in the midst of what fleeting summer there is in the Arctic circle, large patches of snow still speckled the mountains. The crowning cradle of Tuolpagorni held a field of white; not a glacier, as I first thought, just a huge field of surviving snow.

We climbed almost imperceptibly as the day progressed, until we reached our first checkpoint, the Kebnekaise Mountain Lodge, a hive of activity where many had chosen to pitch their tents. But we carried on, leaving the birch forest behind and emerging on to treeless mountain tundra where the weather turned from sunny to solemn as if to match the switch in the landscape. Clouds filled the sky and the wind picked up. We were in the arena of the mountains now; angry rivers boomed through deep canyons, crossed by secure but shaky suspension bridges, and the peaks which had seemed distant all day now loomed all around us.

Before long we were practically at the foot of Tolpagorni, where we made our first camp at the confluence of two streams amid a vast meadow of dancing green tussock. We prepared food together, chatting and laughing as we tipped boiled water into foil cartons of nutritious dust and ate the results, before retiring to our tents. At this high latitude it was still light enough to read at 11pm.

The next morning I woke up to a rainbow stretching in an unbroken arch across the face of the nearby mountains. Tendrils of cloud writhed around the tops of Tuolpagorni and its neighbours. Blue sky and sunshine stretched behind in the direction we had come from, but the route between the mountains ahead sulked in cloud.

We walked onwards, flanked on either side by sublimely ominous hills. Both the Scandinavian and Scottish mountains are prodigiously old, and share a geological ancestry in the form of the Caledonian Oregeny, a period of mountain-forming that happened roughly 490-390 million years ago. The family resemblance is easy to spot in the familiar shape of the hills – the sculpted, weather-beaten look betraying long millennia of erosion, but with myriad scars in the form of plunging corries and dark cliffs left over from the mountains’ youth, when they could have squared up to the Himalayas. Above us waterfalls tumbled down high walls of dark rock, the upper limits of which disappeared into cloud. It was atmospheric and spectacular, Glen Coe without the A82.

Fjälls and Fells

‘Fjällraven’ is the Swedish name for the arctic fox, which is native to Arctic regions including parts of Scandinavia. The word ‘fell’, which we use for mountains in the Lake District, northern England and sometimes in Scotland, derives from ‘fjäll’ – the Old Norse name for mountain. It came from the Vikings! Similar words exist in Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese.

The Kungsleden

The Kungsleden – or King’s Trail – is one of the world’s finest long- distance routes. Established by the Swedish Tourist Association in the early 20th century, it covers almost 400km/250 miles, between Abisko (the end point of the Fjällräven Classic) and Hemavan. Ambitious backpackers can walk the full route but it’s also possible to drop in and out at other points.

We arrived at the next checkpoint, Singi, to be greeted with irrepressibly cheerful volunteers and suovas – a flatbread filled with reindeer meat, mashed potato and lingonberry jam – served from a makeshift kitchen tent. One of the volunteers serving them had a familiar accent, and I asked where she was from.

“Leeds,” replied Lynne Willimott. British people were a bit thin on the ground at this event, but Lynne’s enthusiasm alone seemed to make up for it. This was her fifth visit to the Fjällräven Classic, and she was positively evangelical. “I walked it in 2007, and then have come back every year since to volunteer,” she said. “It’s just amazing up here. The sky is huge. The mountains are awesome. We just don’t have real wilderness like this in Britain.”

Now on the route of the Kungsleden, we carried on through a stunning wide glacial valley to reach Salka, a collection of backcountry huts run by the Swedish Tourist Association. Scandinavians, I decided, know how to enjoy themselves in the wilderness. The volunteers were doling out unfeasibly good carrot cake and coffee and had even hidden stashes of beer around the site, an alcoholic treasure hunt. And next to the burbling river which wound around the site was a sauna. Yes, a sauna. Never has a rudimentary bothy seemed quite so rudimentary.

Sweden doesn’t share our traditional reserve when it comes to human bodies – their saunas are mixed gender and partaken au naturel. Fleshy shapes moved around behind the steamed-up windows and every now and again people emerged from the hut and ran to and from the water with the urgency you’d expect from someone who is more than 100 miles inside the Arctic Circle and splashing around in a mountain river with no clothes on. As it turns out, perspiring heavily while sat unclothed in a small room with a dozen other people as a large German man pours hot water over steaming coals and the occasional naked person runs past the window is nowhere near as weird as it sounds. I returned to my tent with a wistful feeling that the next time I did spend a night in a bothy, it wouldn’t be quite the same.

The sun had returned as we made our way up the Tjäktja pass, a stiff but relatively short climb to reach the high point of the walk, the Tjäktja hut, at 1140m. The view back down the Tjäktjavagge valley was perhaps the best on the walk. We ate a lunch of reindeer cheese and bread while soaking it all in, trying not to wake up two snoozing ultra-runners. From here we crossed the most austere part of the hike, a Mars-like, rock-strewn plateau which eventually gave way to reveal a cinematically beautiful view down-valley towards Alesjaure. This walk was starting to feel like one of those rolling scenic movies that tourism companies use – every brow, summit or turn revealing another awesome panorama of broad glacier- carved valleys, winding rivers or white-speckled mountains.

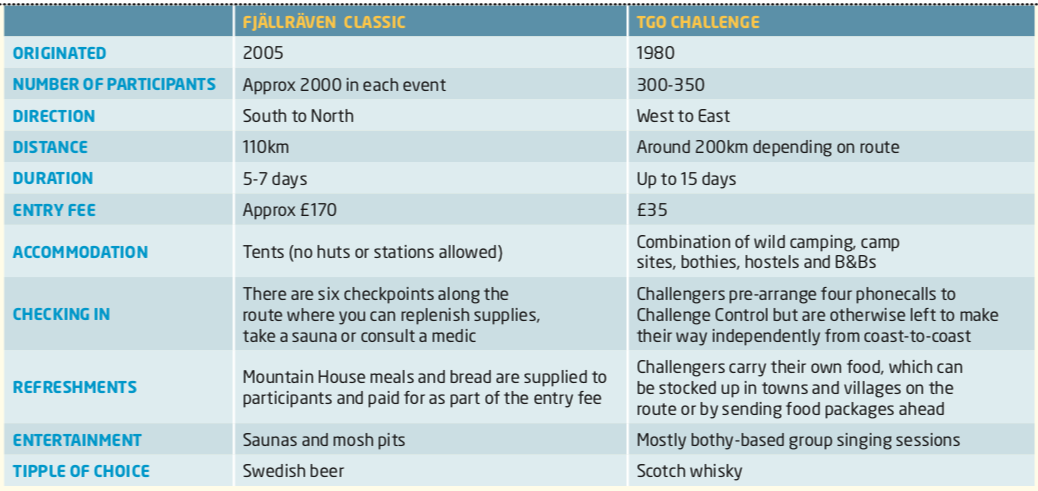

The Fjällräven Classic vs. the TGO Challenge

The Fjällräven Classic and TGO Challenge are both members of a rare breed as non-competitive, sociable long-distance walking events (if you know of any others, drop us a line!). Both offer opportunities for fantastic independent adventure but they do differ from each other in a number of ways…

Click on image to view full size

We stopped by the river at the next checkpoint, where a mini-crowd had gathered to rest a while. The walk was starting to take its toll on some of the participants – mosquito bites were being nursed, aching backs massaged, blistered feet dipped in the cool mountain water. We met a dishevelled German father who was evidently having problems motivating his 15-year-old son and his friend to carry on. “He was having a mental problem,” he said of his child, which possibly got misshapen in translation somewhere. “I had to carry his backpack for a while. Then he was fine.” Kirsten from Denmark, a 76-year-old member of our group, was going slow but strong.

Our camp that night was at Alesjaure checkpoint. Perched on a large promontory where the estuary of a winding river meets a large lake, it appeared in the distance long before we actually reached it. Local Sami had set up a makeshift reindeer restaurant just before the checkpoint – signs as we approached promising reindeer kebabs in five, then three, then two kilometres were some of the canniest marketing I’ve ever seen. Sitting round an open fire, swatting away mosquitos, we met two Swedes who were attempting to complete the walk in less than 24 hours. Bad footwear, rough terrain and a few other mishaps had put paid to that – 40 kilometres to go and it had already taken them 26 hours.

The view from our camp that night was stunning, as it had been the previous two nights – whaleback mountains emerging from the lake shore, a smattering of red Sami cabins next to the water – but it was hard to admire it through the dense cloud of blood-sucking insects. We had at least partially brought this frenzy on ourselves, cleverly erecting our tents next to a small bog that was obviously serving as a breeding ground for Sweden’s entire population of mosquitoes. We made dinner wearing as many clothes as possible, but it was impossible to resist the onslaught. I discovered they had a particular taste for my forehead. Zipping up the tent that night felt a bit like barricading the door of the besieged house in a zombie movie.

We packed up the tents the following morning in a frenzy of swearing and arm-waving and continued walking as soon as possible. The crux of the journey was now out of the way, and from here onwards the gradient was either relatively even or downhill. As an added bonus, the early morning cloud burned away until only wisps remained and we found ourselves basking in stunningly hot sun. Walking along the banks of the lakes that wind down from Alesjaure, past sandy beaches sloping into tropically turquoise water and rocky outcrops surrounding clear pools, it felt more like the coast of Corsica than somewhere in the Arctic Circle. I couldn’t help but stop for a short swim (very short – it might have been blissfully warm outside but water that is solid ice for at least seven months of the year is never going to be balmy). A little while later we saw the German father once more – his son looked to be having a ‘mental problem’ again, throwing his pack to the ground and walking dejectedly along the path with his hood up.

On our descent to the final checkpoint at Kieron, we crossed the treeline again, and noticed a strange thing. Almost all the trees in the forest below us, except at the very high margins, were winter-bare. We puzzled over this for a while. It was definitely not winter. Could the trees here lose their leaves in summer, like some do in very hot parts of the world? Hardly likely – it wasn’t that hot. Could humans be responsible somehow?

A guide finally provided an explanation. The culprit was actually something much smaller. Every seven years or so, millions of moth larvae which have been growing underground emerge into the world. They have a taste for birch trees, and in their hunger devour huge tracts of the forest. It was an astonishing fact – the devastation seemed to stretch as far as the eye could see along the length of the valley. I was amazed something so small could have an impact which looked so human-sized in scope.

Taking part in the Fjällräven Classic

(Ed: all information was correct at the time the issue went to press; consult classic.fjallraven.com for more up-to-date info.)

- There are 2000 places available on the Fjällräven Classic, and participants are encouraged to register as early as possible in order to secure a place.

- Participants start their walks in staggered groups, of which 2012 there were eight, ranging from a start time of 9am on the first day, to 1pm two days later. When you register you will be asked to state which start group you would prefer to be placed in.

- The walk follows the well-known Kungsleden (‘King’s Trail’) from Nikkalokta in the south, finishing 110km to the north at Abisko.

- The nearest airport and train station to the start point are both in Kiruna and a bus transfer from Kiruna to the start of the event is included in the application fee.

- You can travel to Kiruna from Stockholm by plane from Arlanda airport (90 minutes, Scandinavian Airlines: www.sas.se) or sleeper train (www.sj.se). Four airlines – SAS, British Airways, AerOlympic and Norwegian – fly from the UK to Arlanda.

- There are trains and buses from the finish point of Abisko Mountain Station back to Kiruna.

- Full information about the event is available on the Fjällräven website at classic.fjallraven.com.

Our final day involves an easy but pleasant walk through the boreal forest of the Abisko National Park alongside the Abiskojåkka river, which varies from a wide, emerald green flow in its upper reaches to a booming white torrent as it constricts itself through narrow canyons further down. We rest for a moment on the rock next to one of these rapids, only a kilometre or so from the end. I am tired, sunburned and covered in mosquito bites, which run like Braille up my arms, over my back and into places I didn’t even think they could reach. My forehead is covered in enough lumps to allow me to pass off as a Klingon. But I feel elated, and we all agree it’s been a sublime and unforgettable five days. Shortly before the finish we pass under the entrance gate to the Kungsleden – even as this walk is ending it seems to hold out the prospect of another.

All the participants get a round of applause as they cross the finish line in Abisko, and we are no different. Led by a triumphant Kirsten, we end the walk to the sound of cheers and clapping. We collect our medals then settle down on a table in the sun to a beer, a reindeer kebab and a long sit. We clap others as they pass over the finish line. Some punch the air as they finish, some run, some put on a choreographed show – one burly group of men holds hands and skips down the final few yards – and some look confused because they’re just passersby receiving an unwarranted round of applause. And we see acquaintances from earlier in our journey cross the line – including a certain German father, a short distance after his smiling, and evidently quite relieved, son.

All the participants get a round of applause as they cross the finish line in Abisko, and we are no different. Led by a triumphant Kirsten, we end the walk to the sound of cheers and clapping. We collect our medals then settle down on a table in the sun to a beer, a reindeer kebab and a long sit. We clap others as they pass over the finish line. Some punch the air as they finish, some run, some put on a choreographed show – one burly group of men holds hands and skips down the final few yards – and some look confused because they’re just passersby receiving an unwarranted round of applause. And we see acquaintances from earlier in our journey cross the line – including a certain German father, a short distance after his smiling, and evidently quite relieved, son.

Behind us there is a tent with a bar and a stage inside – later on I will find myself flouting Sweden’s stringent health and safety regulations pertaining to crowd-surfing. But for now we sprawl out amid the birch trees savouring the hot summer sun, with incongruously snow-flecked mountains in the distance, while a band sings the famous line: “And all the roads we have to walk are winding…” Indeed they are, but what better way to walk them than with a pack on your back, with newfound friends, through the magical mountains of Swedish Lapland.

Header image © Carey Davies