Emily Rodway takes a walk over Striding Edge with Britain’s most famous mountaineer

In our Spring 2018 issue, celebrating 40 years of The Great Outdoors, we’ve invited four former editors (Roger Smith, Peter Evans, Cameron McNeish and John Manning) to write a bit about what their time at the magazine meant to them. But those features don’t tell the whole story of TGO’s editorial team.

Our current Editor is Emily Rodway, who was been at the reigns since 2010. There wasn’t space in the latest issue for her to add her own editor’s story, so instead she has selected this feature – one that perfectly sums up why The Great Outdoors is special, and what serving this magazine means for her.

By Emily Rodway. First published in the January 2010 issue.

There can’t be many finer ways to spend a sunny morning than striding over Helvellyn. But when you’ve been climbing mountains for 58 years; are lucky enough to enjoy annual visits to the Lofoten Islands, Australia, Spain and Morocco; and have led some of the most incredible Himalayan expeditions in history… in short, when you’re mountaineering legend Sir Chris Bonington – some might assume the magic of a day’s walk in the Lakeland fells would have worn off. They’d be wrong.

Walking over Striding Edge with Chris Bonington is exhilarating – not just from the buzz of knowing you’re in rather special company, but because, on a clear, bright day like today, the expression on Bonington’s face says it all: it really doesn’t get much better than this.

Britain’s most famous mountaineer has lived in the Lake District for 35 years and loves the area passionately: “I think it’s as beautiful as anywhere in the world,” he says. Even so, it’s good to know that, with nearly six decades of mountaineering experience behind him, Chris can summon up so much enthusiasm for what is, in the Bonington scheme of things, a humble wee local stroll. Six days previously, he was on Mont Blanc. Earlier in the year, he was at Everest base camp. In May 2010, he’s leading a trek to Annapurna. Bonington may be 75, but he hasn’t given up on the adventurous stuff.

So how much time does he actually spend climbing and mountaineering these days? “Quite a lot!” he admits with glee. “Probably more gently than I did some years ago, but in an average year, we go to Australia to see my eldest son and grandchildren (and I make sure that I have plenty of trips into the Blue Mountains to go climbing); we go to Spain a couple of times a year (when my wife Wendy plays golf and I go climbing with Catalan friends of mine); I try to go to Morocco every year for about 10 days (there’s a little group of us who have been going for years: Joe Brown started it some 20 years ago); then I try to get out to the States; and I’ve also been going to the Lofoten Islands every year. So yeah, quite a lot!”

It’s hard not to be impressed when he starts cheerfully reeling off the lists of annual adventures. But there’s one trip in particular which Chris is particularly looking forward to – and that’s a forthcoming trek in the Annapurna region that he’s taking part in with his son’s company, Bonington Treks. This has been timed to mark a series of landmark dates: the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Annapurna I by Maurice Herzog; the 50th anniversary of the first ascent of Annapurna II by Bonington himself; the 40th anniversary of the Annapurna South Face ascent, which was the first Himalayan expedition he led; and 25 years since Bonington reached the summit of Everest.

As part of the celebrations to mark these anniversaries, Chris will accompany his son and a group of clients on a 22-day trek to north Annapurna. It looks likely to be a moving experience. “I think what to me will be the emotional thing is the memories of what it was like then. Manang, from what I’ve heard, has changed immensely – where it was an incredibly dirty but rather quaint and attractive little village in 1960, it’s now a prosperous little town. That is progress and it’s improving the quality of life of the people who live there. But yes, there will still be those nostalgic memories.”

When Chris Bonington first visited Nepal, Kathmandhu was yet to develop any tourism infrastructure and trekking hadn’t been invented. Bonington, who was then an Army officer, travelled over on an ocean liner, accompanying the team’s expedition gear, as part of a joint British/Indian/Nepalese Services Expedition. On nearing the summit of Annapurna II, he was chosen – along with Sherpa Ang Nyima and Captain Dick Grant – to attempt the summit. The attempt was successful: they made the first ascent. As Bonington explains, what makes the forthcoming Bonington Treks trip even more special is that two of the people who’ve signed up for it are Captain Dick Grant’s son and grandson. “Sadly Dick died of cancer some years ago, so that’ll be quite an emotional thing for me – and it’s fantastic doing it with my son Daniel as well. I’m really, really looking forward to that.”

“Your modern climber is much more of an individualist and the activity is much more of an individual sport”

The 1960 Annapurna II trip was Bonington’s first Himalayan expedition – but he’d been climbing since the age of 16, when he and a friend hitchhiked from London to Snowdonia to tackle their first mountain: a winter ascent of Snowdon. They were unprepared (didn’t know how to read the map properly), under-equipped (wearing their school Burberry jackets) and ended up getting avalanched. The friend returned to London the next day but Bonington stayed in Wales and started dreaming about becoming a climber. By the time he summitted Annapurna II ten years later, he’d already completed several ambitious climbs in the Alps, including the first British ascent of the South-West Pillar of the Dru. The schoolboy’s dream was fulfilled but there were much greater achievements to come.

Not long after Annapurna II, Bonington’s Army career was cut short when he was refused leave to go and climb Nuptse, the third peak of Everest. He later had a brief spell as a management trainee with Unilever, curtailed in a similar fashion when he was refused leave to take time off to go climbing in Patagonia. From then onwards, he was to dedicate his life to mountaineering and adventure – as a journalist, photographer, speaker, and most famously as a climber and expedition leader: bringing together his passion for mountains, his gift for climbing and his logistical and leadership talents to facilitate some of history’s most renowned mountaineering feats.

In 1970, Chris Bonington led the first ascent of the South Face of Annapurna, a demanding expedition which saw Dougal Haston and Don Whillans reach the summit. In 1975, in what he describes as a “complex, challenging intellectual and physical challenge” he led the British Everest Expedition to success when Doug Scott and Dougal Haston reached the high point of the world via Everest’s South-West Face. Two years later Bonington and Scott made the first ascent of the Ogre.

“Of course I didn’t have the faintest bloody idea what I was going to do when I was older! But here I am, aged 75, still working, still loving it”

Looking back on that incredible period, Bonington says: “I think we were incredibly lucky, that generation, that there were still these big obvious challenges to go for – like the South Face of Annapurna, like the South-West Face of Everest. There were a lot of very big, exciting mountains that either had unclimbed facets or were unclimbed.” However, he acknowledges that there was more to the achievements of that era than the fact that the mountains were there, waiting to be summited. There was the talent of the climbers of course, but there was also something else. “These incredible challenges actually required a high level of teamwork, people working together to achieve success on them. And in the early 1970s there was still, perhaps, a vestige of the teamwork and the element of self-discipline that was needed to survive the Second World War; there was still a bit of that. And the considerable austerity that came from immediately after the war went on well into the late fifties. I think all of those things helped people work together.”

And what of Bonington himself? Where did he find the strength of character to bring the right groups of mountaineers together, lead such demanding expeditions, and cope when things went wrong – particularly when people lost their lives on the mountains? “I’m not sure,” he admits. “I mean… I’ve got it and I can cope and I suppose that comes from a mixture of genes, what happened to you as a child, and everything else.” It’s hard to imagine what it must feel like to have lost so many friends along the way – people with whom he shared the most challenging of experiences. Does he spend much time these days thinking about those who have been lost? “You miss them,” he says simply, the emotion written on his face. “They’re always there, at the back of your mind.”

Today’s top level mountaineers encounter the same risks, but Bonington believes their approach is significantly different – and that is partly down to changes in society itself. “The objectives have changed,” he says. “To achieve an identity and do something new, people are getting into speed climbing, BASE jumping and all these extraordinary things which require incredible skill and a lot of commitment. There is also a social factor too – linked to the whole Maggie Thatcher thing and everything else – of people doing things for themselves, for personal gain, personal profit. Your modern climber is much more of an individualist and the activity is much more of an individual sport.

“You get the same kind of thing in guided climbing, going up Everest. One of the problems is that all those people who go up Everest, their one objective is to get themselves personally to the top of the mountain. Whereas, on the 1975 Everest expedition, Tut Braithwaite and Nick Estcourt were prepared to sacrifice their chances of getting to the top of the mountain by exhausting themselves and pushing to get up the rock band. You needed that element of self-sacrifice and I think that isn’t present any longer.”

Yet Bonington is impressed by the current generation of mountaineers; people who “are doing incredibly bold, alpine style routes in the Himalayas”. He particularly rates Mick Fowler – who he describes as one of the greatest mountaineers this country has ever known – and Leo Houlding, a man who he considers a good friend, despite a 46-year age gap (although Houlding is considerably younger than his sons, Bonington points out that he is older than his grandchildren!). Perhaps he sees something of himself in the 29-year-old – he commends the younger man’s natural leadership abilities and the fact that he has become an ambassador for the sport. They have only actually climbed together once, for a film in which Houlding interviewed Bonington while they were climbing. But Chris says he’s quite sure they’ll have the opportunity to partner each other on a climb again soon.

He never trains, because he finds it boring, and keeps fit simply by carrying on climbing and hillwalking

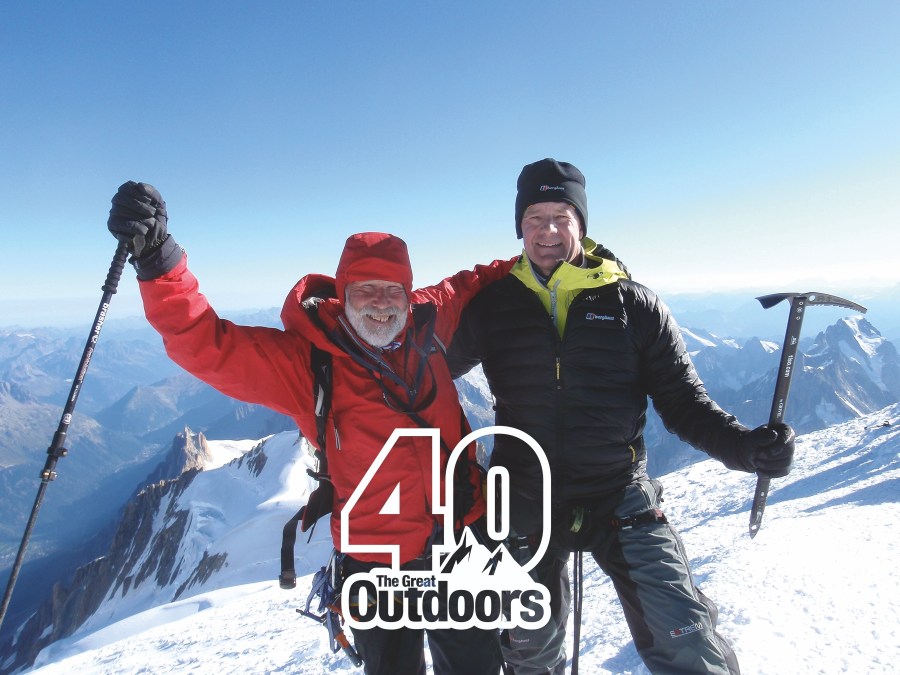

The incredible thing is that you could count Bonington himself among today’s contemporary mountain climbers. His ascents may be modest in comparison with Fowler’s and Houlding’s – and his own expeditions of the 1970s and 1980s – but there’s no question of Chris Bonington giving up mountaineering just yet. The last time he made a first ascent of a Himalayan peak was in 2004 (an Indian mountain of 5,490m in the Menthosa Range); the last time he christened a new climbing route was in Morocco in 2008. But he says the most challenging recent trip was the Mont Blanc one – taking the so-called “Cosmique Route” up the mountain from the Aiguille du Midi, with Berghaus boss Richard Cotter (Bonington is the brand’s Non-Executive Chairman). “Physically it was very, very hard. I was very tired. And yet, when you’ve pushed yourself really hard… I didn’t enjoy being so tired but what I did enjoy was the fantastic situations and the beauty of the mountains. And then when you’ve done it all, there’s a vast sense of satisfaction.”

And that’s why he does it: that’s why he’s always done it. For Chris Bonington, there are so many pleasures to be gained from mountaineering – enough to make it worth the risk and the potential heartbreak. “I love exploratory climbing,” he says, “whether it’s doing a new route in this country or doing the ascent of a peak. Sometimes it’s just looking at a photograph or at a map and saying, yes, that would be a really interesting place to go to. And then getting there, and looking at it for real, and saying this is how I think we could do it, this is the route we can take. That to me is the fascination, and then going there and doing it, actually achieving it and getting to the top.

“When I was climbing well, there was also the pleasure of the rock climbing and ice climbing, when you’re in complete command of your body – and the combination of the risk; of taking judgements. When you’re say 15 to 20 feet above your last runner, and you look at this bit of rock and you work out how to do it (at this stage you probably can’t reverse it anyway). And then, using your skill to actually do it and achieve it – yeah, you get a little frisson of fear too. All of those things… when you finally climb to the top, it gives you a terrific, euphoric sense.”

Bonington acknowledges that he’s fortunate to continue having the opportunity to experience the pleasure of doing what he loves. He never trains, because he finds it boring, and keeps fit simply by carrying on climbing and hillwalking. He says that having so many friends who are considerably younger than himself helps to keep him young. It obviously works: it’s easy to forget Bonington is 75 years old when you observe him swinging his trekking poles over Striding Edge.

However, he also admits that the pleasures of mountaineering are not quite the same in his eighth decade as they were in his youth. “When you were climbing at the height of your powers, you were drifting up climbs. You get to a certain age and you’re stiff, you creak up climbs. Old age is a pig but it’s there! You basically make the most of the things you can do. There’s no point in feeling sorry for yourself.

“But I’m infinitely more cautious now, and the reason is quite simply that in your 30s, even in your 40s, you’ve got a huge amount of stamina – combined, by that age, with experience – to get yourself out of really difficult situations. At 75 I’ve not got that stamina – I haven’t got that agility either, so you cannot cope with those desperate situations. I try to avoid them! But I still love being in the hills, being in the mountains – you trim down the things you’re going to do to what you’re physically capable of. And then I think what’s important is that you always push yourself a bit.”

He keeps up a good pace during the day’s walk on Helvellyn: he’s not storming ahead, but the tempo suits me. And who wants to hurry on a day of glowing colours and expansive views?

So how will he cope if it gets to the point where his body won’t let him continue heading into the mountains – will he find that hard to bear? “I think probably not. Basically in life, you accept the situation you’re in. As long as you can keep your mind – whether I do more reading or whether I get back to doing a bit of writing or what have you… When you can be less physically active, you try to be more mentally active.”

There are plenty of opportunities for mental exertion when you’re Britain’s most famous mountaineer. As well as his position at Berghaus and his speaking engagements, Bonington has associations with numerous charitable organisations. He acknowledges the responsibility that comes with his status and says “you need to do your level best to help the sport that you love”. As such, he’s a trustee of the Mountain Heritage Trust and Outward Bound and a past president of the BMC. He’s also patron of Doug Scott’s charity Community Action Nepal, Vice President of the Youth Hostels Association, honorary Life Vice President of the Campaign for National Parks and President of the leprosy charity Lepra: “When people ask me to help them, if I can, I do,” he says.

Having spent a few hours in his company, it’s easy to see why Bonington has had such success as a public speaker. I’m not sure what I expected exactly, I suppose that he’d be a bit grander, a bit less accessible – but in the flesh he is warm, exuberant and funny. He doesn’t take himself too seriously either. Talking about the forthcoming Annapurna trek, Chris confesses that navigation is not his strong point (“but I think I can find the way next year!”) while, in reference to his climbing partner and long-term friend Doug Scott, he says: “It’s great climbing with Doug because we climb at about the same kind of a standard and we’re about equally decrepit!” I’m not sure what Scott, who’s a few years Bonington’s junior, would make of that comparison, but Chris Bonington is clearly far from decrepit. He keeps up a good pace during the day’s walk on Helvellyn: he’s not storming ahead, but the tempo suits me. And who wants to hurry on a day of glowing colours and expansive views?

Earlier on, when we were part of a larger group, Bonington was asked by one of the organisers if he would be happy “bringing up the rear” for the crossing of Striding Edge – he was so enamoured by the prospect of keeping an eye on those at the back of the group, you’d think he’d been offered a fat slice of cake. Then, as we drop down Swirral Edge over crampon-scratched rock, he asks whether I’ve crossed Helvellyn’s ridges in winter conditions. I haven’t yet, but when I do, I’ll know the experience comes heartily recommended. Nobody could accuse Bonington of showing lack of enthusiasm when it comes to mountains.

I ask him if there’s anything he wishes he’d achieved – or indeed, anything he still hopes to achieve, in his mountaineering career. “No, not really” he says. “I’ve got no regrets. I think my ambition is to be able to go on climbing and enjoying the mountains for as long as I possibly can.”

And what would his younger self have thought if he knew he’d still be mountaineering at 75? “In your 30s, you look at someone who’s in their 60s and you think they’re totally and utterly past it. I remember, when I started as a freelancer making a living out of climbing – lecturing and writing and so on – I spoke on the ladies’ luncheon club circuit. This was in the early 1960s and I was getting paid about £10 a lecture. And these lovely ladies, they said [Bonington adopts a high-pitched, quavering voice]: ‘Oh dear, I see what you’re doing now, but what are you going to do when you’re older?’ Of course I didn’t have the faintest bloody idea what I was going to do when I was older! But here I am, aged 75, still working, still loving it – I wouldn’t want to retire. I’m doing much the same thing as I’ve always done.”

Look out for more Editors’ Stories over the coming weeks, and don’t forget to pick up a copy of our latest issue to read