Sarah Hobbs’ story (or at least this retelling) begins at Black Rocks, a gritstone outcrop just beyond the Peak District boundary. The site of some extreme climbing routes, it was a stone’s throw from her childhood home and Sarah spent many hours here scrambling and exploring. Adventures with family further afield to the Lake District (at 10 weeks old the deep snow of Latrigg left Sarah forever changed, according to her mother) and Powys walking among hedgerows with her Welsh-speaking grandad who carried bracken to keep the flies away define these formative chapters.

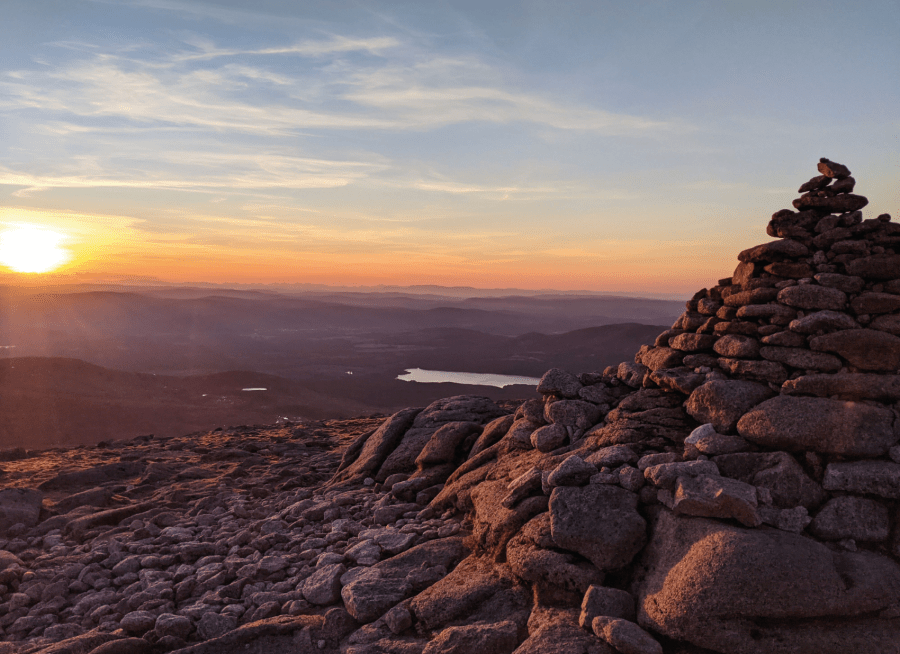

Main image: Sarah hosting a storywalk | Credit: David Lintern

Sarah’s first hill memory is of climbing Catbells and throwing pebbles towards the chimneys of Little Town – an eight-year-old inspired by Beatrix Potter’s Mrs. Tiggywinkle – just to see if they reached. “They didn’t,” she confirmed, adding, “It’s interesting looking back that this memory is so closely linked with story.”

For most of Sarah’s life, she’d worked in London with minority communities to draw out the silenced voices and hidden stories in systemic health and education inequality. But the landscape – and how feeling small among mountain giants can help one “maintain both humility and mortality” – called. Now 38, Sarah guides folks on her Strathspey Storywalks into Am Monadh Ruadh (Cairngorms) from Aviemore where she has lived since 2016.

Sarah tells us about herding reindeer, walking hills whose names she couldn’t pronouce and how she came to immerse herself in the landscape and Gaelic language through her Strathspey Storywalks which connect people and place, folktales and ecological insights.

TGO: Can you recall your first, formative experiences of the outdoors?

Sarah: My parents took me up hills across the Lake District and Wales from the age of 10 weeks – Latrigg in deep snow to be precise. My mum thinks I’ve never been the same since. My first hill memory is climbing Catbells age eight and throwing pebbles towards the chimneys of Little Town, as Beatrix Potter wrote in Mrs Tiggywinkle, just to see if they reached (they didn’t). It’s interesting looking back that this memory is so closely linked with story.

On holidays in Powys, my grandad, a Welsh-speaker, as we wandered down evening hedgerowed lanes, would always cut himself a bracken with his penknife and carry it over his head ‘to keep the flies away.’ Still the smell of bracken reminds me of him. Growing up in Derbyshire, Black Rock was very literally on our doorstep and I spent time scrambling about there, and exploring the woods and hills – mostly solo, as my friends weren’t that keen!

At 16, I was awarded a scholarship to study at college in Norway for two years, so being on the west coast of Fjaler Kommune surrounded by mountains beside a fjord certainly helped form a landscape of ‘home’, begun in Derbyshire, and later sought in the Highlands. There’s something about feeling small and insignificant in these landscapes which is great for perspective, maintaining both humility and mortality.

TGO: How did you come to love the landscapes of Scotland, specifically?

Sarah: I distinctly remember travelling through Aviemore in 2000, with my jaw on the ground thinking, what IS this strange, run-down, place? So it’s really comeuppance that I ended up here – now changed in many ways, the village and myself, and I love it here. It’s my home, and the reindeer brought me! There are many ex-reindeer herders now living in the strath as we can’t tear ourselves away. It gets into your bones! I first volunteered with the herd in 2013, accompanied by a copy of the Living Mountain, which I felt exhilarated and validated by – I wasn’t alone in exploring places ‘differently.’

Spending all day every day in the Cairngorms, and with Highland folk being so unassuming and welcoming, so it was that I finally moved up in 2016 – a world away from my London life working with minority communities in systemic health and education inequality.

TGO: What was your first experience of both Gaelic and the great Scottish storytelling tradition?

Sarah: Every evening at Reindeer House I would chuck open the map on the kitchen table and plan my evening walk. Mostly this involved hill names I could not even pronounce, let alone know the meaning of. It wasn’t long before broadcaster, storyteller and writer Ruairidh MacIlleathain introduced me to both Gaelic in the landscape and stories in one fell swoop, rather improbably on a course in Aviemore school gym, and I’ve not looked back.

I’ve come to feel it’s a real personal responsibility to learn Gaelic, especially as an English person choosing to live in the Highlands. It can’t repair what’s done, but it changes what goes forward.

TGO: What is it about storytelling that ‘unlocks’ landscape, in your opinion?

Sarah: All the layers of people who have lived there, alongside fairy folk, giants, creatures such as kelpies, all the lore of the land and sky – and indeed how connected that is – immediately gives new perspectives on the view you’re looking at, the road you’re standing on, the tea you’re drinking.

As ever, the thread throughout my life has been the quiet or silenced voices, the ‘gaps’ in the landscape, so even though there may be no visible or obvious signs left, the story still stands. And stand it should, especially as we grapple with for example the ongoing legacy of colonialism, how the Highlands benefited – and lost – from it (many towns, schools and hospitals here were built on the spoils of the slave trade but also the current pattern of über-concentrated land ownership, an English colonial legacy post-Culloden, perpetuates inequality in rural communities to this day) and how people from here had a central role in violently and purposely decimating the lives and culture of indigenous peoples for example in Canada and Australia, which again remains an open wound to this day.

I am aiming to tell more of a whole story, more of a connected story, with both people and place, near and far, which then changes how we see, and possibly how we act.

TGO: Could you share your favourite piece of folklore you’ve stumbled upon in your research?

Sarah: This changes on a monthly basis! My current little fascination is that we get the word ‘ghoul’ directly from Arabic, where it means more of a monstrous giant rather than a ghostly spirit. On recently telling a particular Palestinian tale about a ghoul, it turns out there’s a very similar tale from Aberdeenshire! So there’s always more to read and look into.

TGO: For those who may not have experience of outdoor group events, can you describe your story walks?

Sarah: A Storywalk is a journey through and into the landscape; more of it unfurls as we walk along. I prefer small groups to really be able to connect with everyone, and we delve into many aspects, from social history and Gaelic heritage, to folktales and legends, to ecology and foraging. I may also share some of my research work, for example into the wartime ‘lumberjill’ camps of the strath, or the local links to empire, but walks are very much tailored to people’s interests, seasons, and what comes up in conversation.

I find a special spot we can sit and drink seasonal foraged tea – a Bronze Age burial cairn, or a fairy hill – and folk of all ages are welcome. I’ve had toddlers to people in their late eighties! Storywalks are a way to value and respect a place, in all its colours, for both locals and visitors. It’s very much re-storying the land and skyscape with tales that have been passed down by ear for tens, hundreds, sometimes thousands of years, and putting stories back where they belong in the landscape.

Currently I’m also running a fundraising Storywalk which connects folktales from the Highlands with folktales from Palestine, weaving Gaelic and Arabic (which I studied) through stories of community, landscape and heritage, marking historical and ongoing injustice and dispossession as well as the power of story to record, resist, join together and hope.

TGO: How do you tailor walks to groups of differing needs such as young people or those with Alzheimer’s – and what, in your observations, do participants take away from the experience?

Sarah: Tailoring walks involves tweaking the choice, depth or delivery of content, making sure there are enough interactive elements, challenges, more to taste, and adapting along the way. I love to observe (and shape) how the focus of a group evolves over the course of a few hours – a bit like sand vibration patterns – initially a mishmash of wayward grains then forming a cohesive pattern. And the patterns change depending on what story is told…

People who have come on Storywalks mention how much they learn about a place they thought they knew, how captivating the stories are for all ages, and the engagement and connection. I’ve been in tears at several reviews from folk who have really ‘got’ what I’m attempting to do, and have received numerous drawings from children of story creatures, as well as pictures of wee ones stirring big pots of foraged tea on their stoves.

One wee girl said she wanted to do what I do, that she didn’t know such a ‘job’ was possible. This is so galvanising, to inspire all generations to look and experience differently.

TGO: What does the ideal time outdoors look like for you?

Sarah: Up a hill on a small twisty peaty tree-rooty path with a bit of breeze, going slowly, going quietly, but also with impromptu joyful outbursts of song or laughter or just wonder, tasting, smelling, greeting creatures along the way, with views of snow, shifting cloud and regenerating woodland, and heather to lay in or a rock to sit against and just be, accompanied by oatcakes, burn water and bees.

I think it’s heaven, and it doesn’t get better than that.

Follow the story at www.storywalks.scot.