Could a new study be the first step in Britain’s most exciting rewilding project yet? Hanna Lindon takes a look.

Early this year, conservationists launched a year-long study to evaluate the social feasibility of returning lynx to Scotland. Eurasian lynx were driven to extinction in Britain more than 500 years ago by hunting and habitat depletion. Now a group of charities – Scotland: The Big Picture (STBP), Trees for Life and Vincent Wildlife Trust – wants to assess public appetite for the reintroduction of Europe’s third-largest predator.

“This isn’t a campaign to reintroduce lynx, although we make no secret of the fact that we’d like them back,” says Peter Cairns, Executive Director of STBP. “It’s a social feasibility study. The aim is to accurately assess the public and stakeholder support for lynx – or indeed not. And also to identify any common barriers that exist and how they might be overcome with a collaborative approach.”

A key first step

The suggestion that lynx might be returned to the Scottish Highlands and other remote areas of Britain is nothing new in itself. The idea was first mooted in Scotland back in 2008, and in 2018 a proposal to release six animals in Northumberland was rejected by the government. Previous studies have modelled what the reintroduction of lynx might look like in Scotland and estimated how many animals the Scottish countryside could support.

However, this new study is a key first step towards securing an official licence for any reintroduction.

“The process [for reintroductions] is to make a license application from the statutory licensing body – which in our case is NatureScot – and to do that you first have to prove that there is social acceptance and tolerance for any species, particularly a large predator,” says Peter. “So it’s necessary in statutory terms as well as in philosophical terms, because without people’s support the process is much more difficult – if not impossible.”

Lynx in the landscape

The Lynx to Scotland study will begin by focussing on two areas that have been identified as suitable lynx habitat: the Cairngorms and Argyll. Both have large populations of roe deer, which are currently only controlled through human intervention.

“The cost of deer management across Scotland is huge,” Peter points out. “Forestry and Land Scotland spend huge amounts of money culling woodland deer. Then there’s the cost of fencing deer in and out. But lynx are a free and efficient deer management service. They regulate herbivore numbers and ecologically they are recognised as vital drivers of healthy ecosystems.”

Native Caledonian pine forest in the Cairngorms. Photo: STBP

By dispersing deer across the landscape and leaving the remains of kills for smaller animals to feast on, lynx could both control deer numbers and improve biodiversity across Scotland. Ultimately, this could even lead to visible changes to the landscape itself.

“They won’t transform the landscape quickly and there is unlikely to be any radical impact we couldn’t reasonably guess at,” says Peter. “But over a period of time I think they would reinstate ecological processes that are missing across Britain – although in visual terms it will be nuanced and quite slow.”

Walking with wild cats

Lynx to Scotland researchers will be consulting with stakeholders such as farmers, landowners, ghillies, gamekeepers and tourism operators – but the plan is also to canvass the opinion of those who visit and enjoy the Scottish countryside.

Most organisations agree that lynx pose no threat to humans. According to the Lynx UK Trust, there are no recorded attacks on humans by Eurasian lynx anywhere in the world. So what interaction would walkers have with these secretive creatures if they were to be reintroduced to the Highlands?

“A sighting would be a rare event,” says Peter. “You could walk the hills for many years in lynx country without seeing a lynx. They are woodland animals – they rely on cover to stay hidden. That’s not to say you wouldn’t see evidence of them. They tend to stash their prey, so if you were walking up a mountain path you might get a sniff of a roe deer that had been stashed by a lynx. It’s also possible that you could see tracks.”

Despite the low chance of a sighting, evidence from other countries where lynx have been introduced suggests that the charismatic wild cats are a big tourism draw – another argument in support of their reintroduction.

The long road to release

While previous surveys have suggested that the wider Scottish public is broadly in favour of reintroducing lynx, there’s likely to be resistance from local farmers and landowners. NFU Scotland has previously said that “any proposals to re-introduce predators such as lynx or wolves are of huge concern to Scottish farmers and crofters.” The organisation cited reports from Norway of hill farmers giving up stocking sheep due to lynx predation.

Peter believes that these concerns are misplaced. He points out that Norwegian sheep range in forests and that predation is therefore exponentially higher in the Scandinavian country than it is anywhere else in Europe. “A more comparable example might be Switzerland,” he suggests, “where they lose something like 70 sheep per year across the whole country.”

Eurasian Lynx (lynx lynx) in autumnal boreal forest, Norway (c)

Whether or not such opposition is well-founded, it’s still the greatest barrier that proponents of lynx reintroduction must overcome. According to Dr David Hetherington, author of The Lynx and Us, reintroductions to Bavaria and Austria in the 1980s failed because local hunters were against them and many of the released animals were shot. Similar concerns would exist if lynx were returned to Scotland without the support of the rural communities. Could they suffer the same fate as Wales’ last golden eagle?

“This is a conversation that’s been rattling around for many years and various people have tickled it around the edges,” says Peter. “But the bottom line is in order to move it forward this study is an essential step.”

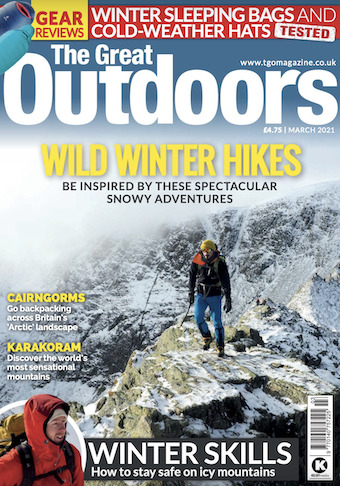

Subscribe to The Great Outdoors

Subscribe to The Great Outdoors

The Great Outdoors is the UK’s original hiking magazine. We have been inspiring people to explore wild places for more than 40 years.

Through compelling writing, beautifully illustrated stories and eye-catching content, we seek to convey the joy of adventure, the thrill of mountainous and wild environments, and the wonder of the natural world.

Want to read more from us?

- Get three issues of the magazine for £9.99, saving 30% with free UK home delivery.

- Take out a full subscription at just £15 for your first six issues.

- Order the latest issue and get it delivered straight to your door for no extra cost.

- Catch up on content you may have missed by buying individual back issues with free postage and packaging.