It’s a golden age for small adventure films – but as EATHIE and COIRE EILDE prove, it isn’t all about adrenaline and record-breaking feats

In recent years, new technologies have led to an explosion of filmmaking at every scale. Ever smaller, lighter and better-quality cameras can be easily taken on challenging expeditions. YouTube allows amateur filmmakers with low budgets to find an audience. Drones can provide wide context shots that would otherwise be difficult or impossible.

But how is adventure filmmaking reacting to these changes? The Great Outdoors got in touch with Mike Webster and James Roddie, the creative minds behind two new short adventure documentaries: EATHIE and COIRE EILDE, each depicting a canyoning adventure in Scotland.

These films don’t feature high-octane, goal-driven challenges; there are no death-defying summits or gnarly grades, no routes other climbers or outdoor enthusiasts would even recognise. These short documentaries are about a more humble form of interaction with wild places. They celebrate the simple experience of venturing somewhere obscure and without human influence – but with the added frisson of climbing and abseiling waterfalls…

About the films

EATHIE

Short documentary about adventure and wildlife photographer James Roddie and his descent of the obscure Eathie Gorge on the Black Isle in Scotland. This is potentially the first time this had been done, though information is hard to find.

EATHIE has been shown at the Backpacking Light Film Festival in Colorado, the Inverness Film Festival, the Cinemor77 film festival tour, and the Dundee Mountain Film Festival.

Watch the trailer:

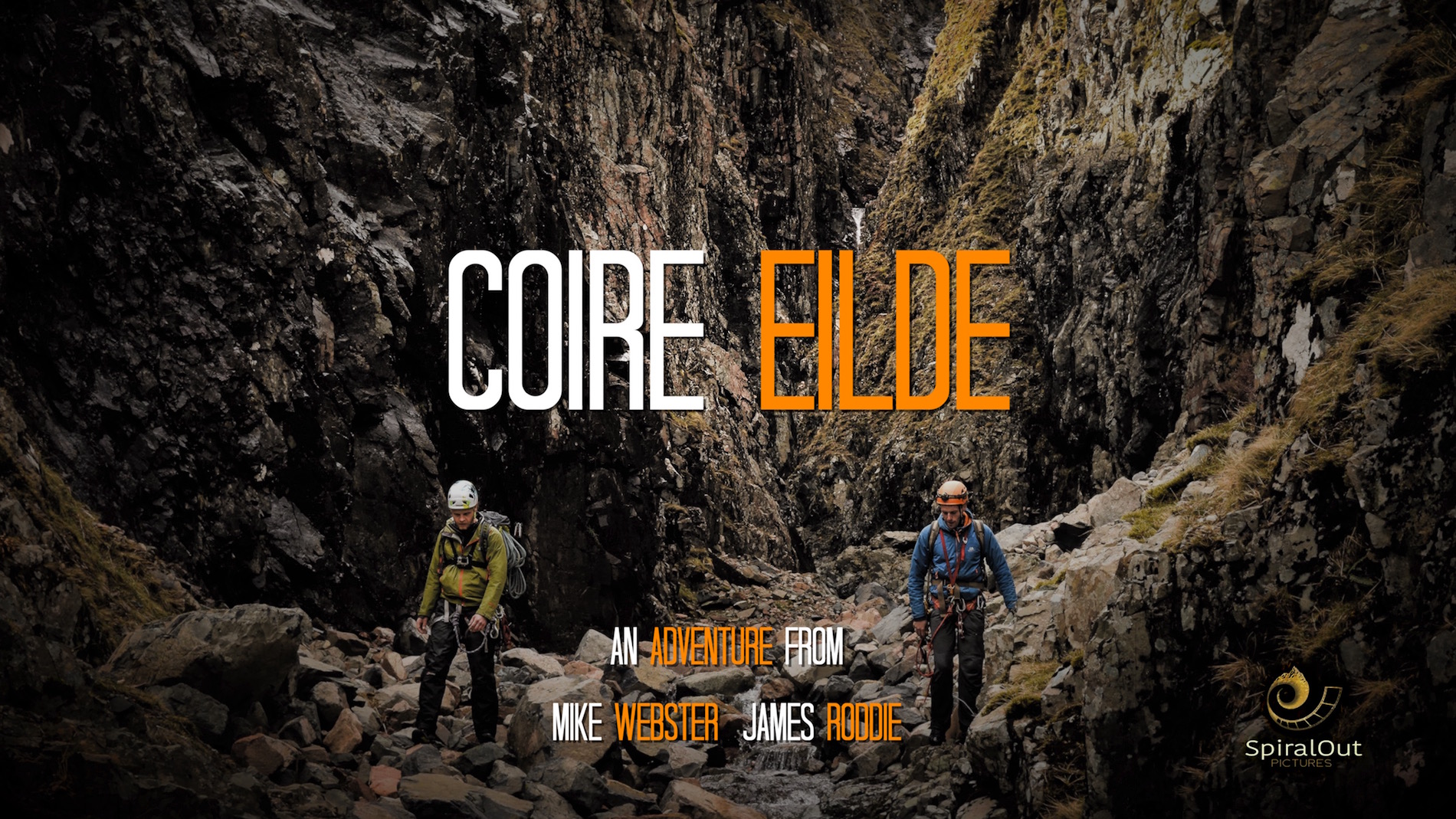

COIRE EILDE

Inspired by winter photographs of the relatively unknown Eilde Canyon in Glencoe, adventure writer and photographer James Roddie sets off to see if he can make the first summer traverse of the gorge.

COIRE EILDE has been shown at the Backpacking Light Film Festival in Colorado and the Inverness Film Festival.

Meet the canyoneers

Mike Webster

“I’m an adventure filmmaker, film tutor and workshop leader based in Inverness. I’ve been making films for about 15 years, since I was at school, but the adventure element is relatively new – since about 2010, when I got in to climbing. Since then I’ve filmed documentaries in Morocco and Peru, and filmed climbing all over Scotland.”

https://mikewebsterdop.wordpress.com/

@BeowulftheDoP

Image by James Roddie

James Roddie

“I’m a photographer and outdoors writer based near Inverness. I teach wildlife and landscape photography, mainly as a guide out on the hills of the Scottish Highlands, and write magazine articles surrounding hillwalking, mountain and climbing.”

https://jamesroddie.com/

@jroddiephoto

[Editor: James is also a contributor for The Great Outdoors – and the brother of our online editor Alex!]

Image by Mike Webster

Tell us about your recent films EATHIE and COIRE EILDE.

Mike: The film EATHIE started for me as an invite from James to join him on the descent, as he had a photo commission to complete. He needed images of someone on abseil, and knew I climbed, so was confident that I’d be competent enough not to kill myself in the process!

James and I had talked about making a film together before, but I just wanted to have fun and make a “wee YouTube video”, as I’m awful for putting too much pressure on myself to deliver a high-end project. By taking the pressure off myself, we had a great time, and ended up with a really good little film. When I realised that our film was better than the “wee YouTube film” that we anticipated, I spoke to Marcus, my drone pilot friend, and we went back a week later for some aerial shots of the gorge to slot in, up the production values of the film, and to give it scale. We then started submitting to film festivals to see if anyone was interested.

James still had another gorge to do for his commission, and he had two in mind. He opted for the Eilde Canyon in Glen Coe as it was more unknown, and that became COIRE EILDE. By this point EATHIE had started to be accepted for film festivals, but I knew we could do things bigger and better film wise than we had on EATHIE.

I very much feel like they are sibling films, and despite their similarities, I’m pleased that there have been a few film festivals happy to share them as a pair.

Both films take place in waterfall-filled Scottish gorges. How did you overcome the technical challenges of filming and photography in the conditions you found?

Mike: The technical challenges of filming for me were simply: how can we keep the kit light and dry? DSLR filmmaking with a basic top microphone added was a simple way forward. The most difficult thing for me was recording good, usable sound, as waterfalls often sound like white noise when recorded. Recording James speaking in those environments is difficult, but you have to just make the best of it. James carried a light tripod with him for certain shots, and I had a monopod, so we helped each other out and all in all it was kept pretty light.

James: An elaborate system of drybags helps keep camera equipment as dry as possible, though there were places in both gorges where a GoPro was the only camera we could use in the conditions. For keeping the cameras safe on the abseils, I use a well-padded camera case inside a heavy-duty drybag which is usually attached to my waist harness with a karabiner.

These kinds of locations are usually quite dark or involve deep shadows, so I tend to use a single, off-camera flashgun for photography in places like this. Careful positioning of the flashgun relative to the camera allows me to fill-in shadows or create new ones in whichever way I wish.

In COIRE EILDE, James describes the gorge as “obscure, intimidating, everything you want from a good adventure”. How did the obscurity of this place affect the experience – both during the planning and while trying to find a feasible route?

Mike: Because we knew there had been relatively few visitors to the gorge – a handful of winter climbers who had abseiled in halfway along – we didn’t know for sure that it was even possible to do the route we hoped to, which was following the gorge from bottom to top.

At the bottom of the first big climb (a dodgy solo on wet, crumbly rock) we couldn’t even see if there was a plausible escape should the route be impassable further up, except retreating and abseiling down the way we’d come up. After that climb, it certainly became less of a worrying issue, even as we became more committed to the route.

James – An air of obscurity helped us to approach both projects with open minds. So many climbing or caving routes have long-established reputations and grades which can heavily affect your expectations – we had the privilege of being free of that in both these gorges. In terms of finding a feasible route through the gorges, the sense of obscurity keeps you on your toes. We were highly attuned to everything around us and were constantly taking mental notes of potential routes of escape, possible belays, and any dangers that we could face.

Tell us about the wildlife and biodiversity you saw in the Eathie Gorge.

James: The Eathie Gorge is a complete jungle! It is filled with beautiful deciduous woodland (mainly birch and hazel) which is probably very old. Due to the inaccessibility of the inner parts of the gorge, it’s highly unlikely that it has ever been totally cleared of trees in the past. There’s roe deer tracks cutting to and fro all over the place, and on a previous attempt at the gorge I came face to face with a tawny owl sat in a tree. The walls of the gorge are covered with a profusion of ferns and mosses and there’s a damp, earthy smell throughout.

The Eathie Gorge is described as almost unheard of, but somewhere that should be better known. Do you think there’s a risk that, as more outdoor pursuits like canyoning gain traction in the UK, fragile environments in previously inaccessible locations might begin to feel the strain? What do you think the role of niche adventurers who seek these places out should be in protecting them?

James: I think that the ‘honeypot effect’ will always apply. In general, even when outdoor activities undergo explosions of popularity, it is usually only a small number of places that attract the majority of people. Take Scottish winter climbing as an example. Participation is at a real high and information on climbing areas is more accessible than ever, yet the majority of winter climbing crags remain very quiet on days when a handful of locations are mobbed.

There is however a risk that fragile environments such as these gorges could start to feel some strain from visitors in the future, so niche adventurers certainly have a role to play in preaching environmental good-practice. We also have the ability to simply not share our adventures with others, and this is certainly something I’ve done on more than one occasion when I’ve been concerned somewhere could be damaged if it became popular. I think that everyone who takes part in outdoor activities can work on reducing their impact on the places they enjoy.

You draw parallels between canyoning and both climbing and caving. Do you think exploring a gorge is more akin to caving than rock climbing, and if so, why?

Mike: I found my rope skills from climbing an asset in these gorges, and our climbing abilities certainly made parts of COIRE EILDE possible where they wouldn’t have been otherwise. For me, being a rock climber, a strong point of comparison surrounds the discovery of the route on the journey. In rock climbing you can usually see the route and end game from the start (apart from long multi-pitch routes). With gorge scrambling and canyoning there is a lot of discovery en route, much like caving.

James: both caves and gorges are wet, noisy, enclosed environments, which usually involve slippery rock and abseiling down waterfalls. In many ways caving and canyoning require very similar skillsets. There are strong parallels with adventurous trad climbing too however – dodgy belays, inventive rope work and the need for a very particular mentality.

In both films, there was every chance you might not have found a feasible route through to the end. How would this have affected your perception of the adventure – a failure or still a success?

Mike: As a filmmaker and storyteller, I’m always looking for a satisfying ending, so it would have certainly affected the films. But with my no-pressure approach I took to the adventure that became EATHIE we would have probably had a different message in the film; classic “It’s about the journey not the destination”-style message. Had it not worked out part-way along I would have been interested to see if we could return and try again; creating a win out of a failure always makes a good story.

For COIRE EILDE I had put more pressure on myself for the adventure and the film. We very nearly didn’t get past that first waterfall, which would have put a dampener on the project and our spirits if we hadn’t been stubborn enough to push on. After that point we were determined not to retreat as much as possible, though we knew it was very likely we’d get to a point of no escape and have to do so.

The main thing for me, after that waterfall, was not to back out without trying, and as long as we’d gone as far as we could safely go, I think I was going to be happy. But again, the bonus of escaping out of the top rather than abseiling down the way we came up was a real spirit lifter.

Mike, any plans for future adventure films you’re able to share with us?

Mike: Things are exciting at the moment. I have several projects on the go…

Firstly I’m working with filmmaker Thomas Hogben making a film about Highland endurance cyclist Jenny Graham, her exploration of the Highland Trail 550 and an insight into her mind. The three of us are also in the early stages of a potentially massive project later in 2018, but I can’t say too much about that yet!

Thomas and I are also working with endurance cyclist Lee Craigie, editing a film about her journey with fellow cyclist Rickie Cotter on the Tour Divide (a mountain bike race from Canada to Mexico). That had a few sneak preview clips at the Kendal Mountain Film Festival, and there’s been some great feedback and buzz around that. In February I’m joining an expedition opening up a new jungle trekking route from Mexico into the Mayan ruins of Mirador in Guatemala, so I’m going to be shooting that. Finally, James and I are also in the early stages of preparing a new project, something different to what we’ve done before – bigger, more beautiful, and more important.

James, how do you see your outdoor and adventure photography evolving over the coming winter and beyond?

James: A lot of my time in the hills is spent helping others to get the images they want, so time spent working on my own material is precious. I’ve not managed to dedicate much time to Scottish winter landscape photography for a while, and I’d really like to try and fit this around photography guiding this winter. My adventure photography has been largely focused on Scottish caving for the past three years, and this is the vein I want to continue. New caves are being discovered in Scotland every year, and I’ve been lucky enough to be one of the first people to visit and photograph these places. It’s an extremely niche subject and very addictive.

Many thanks to James and Mike for these interesting answers. Keep an eye out on their websites for information about the general release of these films, which is expected at some point in spring 2018.