A new book has been published looking at the pros and cons of reintroducing lynx to Scotland. We spoke to the author to find out more

Rewilding has become a hot topic in recent years. The question is straightforward: since Britain’s upland ecology has become severely depleted over the centuries and millennia, should we seek to restore some of the plants and animals that have vanished thanks largely to human activities? But the practical reality is a lot more complex. The jury’s out on where our priorities should lie.

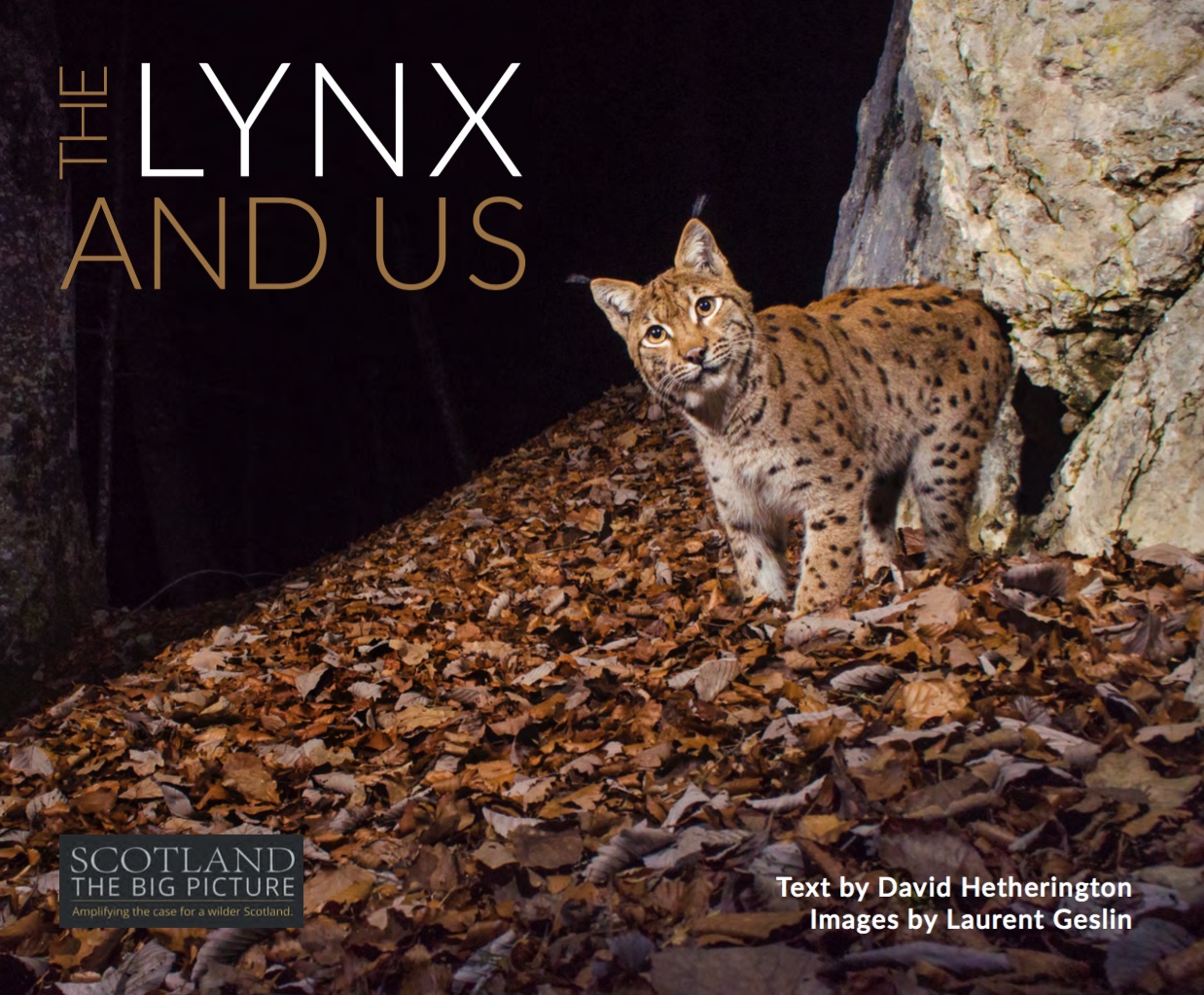

SCOTLAND: The Big Picture, an organisation who describe themselves as ‘amplifying the case for a wilder Scotland’, have recently published a book called The Lynx and Us by ecologist Dr David Hetherington. This book, illustrated by stunning photography of wild lynx by Laurent Geslin, aims to inform a growing debate about the possibility of reintroducing this charismatic predator to Scotland after an absence of more than 400 years. The book draws on evidence from across Europe and examines what it would be like to have an apex predator living in our midst once again.

The Lynx and Us is the second book in a series from SCOTLAND: The Big Picture, following The Red Squirrel: A future in the forest by Neil McIntyre and Polly Pullar. The Lynx and Us is available from www.scotlandbigpicture.com.

To find out more about the lynx and its likely impact in the event of a reintroduction, we contacted the author, Dr David Hetherington.

Please introduce yourself. Who are you and what do you do?

I’m Dr David Hetherington. I’m an ecologist and author, and I live in the Cairngorms. Previously I completed my doctorate at the University of Aberdeen on the feasibility of reintroducing lynx to Scotland.

Your new book, The Lynx and Us, is all about the lynx – and exploring the possibility of restoring this beautiful creature to Scotland. What do you hope this book will achieve?

The book is about exploring the relationship between people and the lynx across Europe. Having done that, it then asks what the implications of that relationship are for Scotland, where there’s a growing national discussion about lynx reintroduction. My feeling is that the discussion is becoming polarised and that there is a lack of unbiased factual information about the species and how it interacts with humans and their activities, so my hope is that the book helps to better inform the discussion.

What are the benefits of returning a small population of lynx to British woodlands?

I think the two most obvious benefits of having a lynx population back in our woodlands are the deer management service they could provide for commercial forestry and native woodlands, and the potential boost they could give to the growing – and increasingly international – wildlife tourism industry.

One lynx will typically kill over 50 woodland deer in a year, especially roe. A population of 400 lynx, which the Highlands is capable of supporting, would prey on over 20,000 woodland deer per year. Forest Enterprise Scotland, which manages around one third of Scotland’s forests, culls 30,000 deer every year with net deer management costs (including culling and fencing), amounting to almost £5 million. And those are just the deer management costs for the public forestry sector – it’s just as relevant an issue for the private forestry sector. Lynx would kill woodland deer day-in day-out, all year round, and don’t charge for the service.

Wildlife watching, and the wider nature-based tourism industry, is a significant and growing element of the Scottish economy, especially in rural areas. Elsewhere in Europe, large carnivores are a major tourism draw, pulling in thousands of international visitors – including from the UK. Here in Scotland we don’t have any of the bankable large carnivores such as bears, wolves and lynx so I think in future we will struggle to compete in this increasingly global business.

Unlike bears and wolves, however, it is virtually impossible to create a guaranteed lynx-watching product – they are too shy, won’t come to bait, and tend to stick to dense cover. The way they contribute to tourism is by acting as a major branding icon. I’ve seen this in several German national parks, where lynx imagery is heavily used to promote an area as being wild and beautiful. People know that lynx are very hard to see but nevertheless they want to be in ‘wild’ landscapes where they know animals like lynx live.

And what are the risks to a successful reintroduction?

The likelihood of a reintroduction ever happening, never mind being successful, will be influenced by how much of an outcry there is from people worried about lynx impacting on their way of life. And as we see from other countries, even if there is a small minority of people vehemently opposed, they can still have an impact on the success of a project if they are prepared to kill lynx illegally. That is why a respectful dialogue, where the concerns of those who live and work in the countryside are listened to and addressed, is so essential. And part of that is making sure that those taking part in the dialogue have access to unbiased, factual information about lynx and how they interact with people.

The rewilding conversation is often focused around the more impressive creatures such as wolves or bears – which many would say are unlikely to return to the UK any time soon. Do you believe there’s a greater chance that the lynx could regain a foothold here?

Studies from around Europe have shown time and time again that, of the three large carnivores, the Eurasian lynx is the species that local people have the most positive attitudes towards. This is largely because lynx are not perceived to pose a threat to human safety and because their impacts on livestock are much easier to control. So yes, I think it’s far more likely that lynx will make a comeback in the UK than bears or wolves.

From a backpacking and hillwalking point of view, the Scottish mountains can often feel eerily barren and sterile – especially once you’ve had experience of travelling through wilder and less damaged ecosystems. How do you think the reintroduction of lynx might affect the experience of spending time in nature?

Yes, that sense that a landscape with lynx in it feels wilder and more special is what drives the marketing of some of the German national parks. Personally, I enjoy walking in landscapes that are more ecologically wholesome and the presence of top predators is the gold standard for good, ecological health.

I always remember the moment I spied, through binoculars, a lynxthat was intently watching me through the foliage from the other side of a wooded gully in the Swiss Alps. It was a radio-collared male that I’d be tracking for a few hours. Without the technology, I would have had no idea it was there watching me all that time. It still makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up just thinking about it now, and that was 17 years ago! Not through fear, as lynx don’t pose a threat to people, but through a momentary but deep sense of connection with such an elusive, wild animal.

What’s your vision for the future of conservation and rewilding in the UK? Are you hopeful or pessimistic?

I’m optimistic. In Scotland as whole, we’re continuing to expand forest cover. There are some fantastic examples of landscape-scale ecological restoration going on, for example in the Cairngorms. A hundred years ago we no longer had red kites, sea eagles, ospreys, goshawks, cranes, or beavers, but now they’re all back. It’s not always without controversy or conflict, but we’re slowly but surely restoring some ecological vibrancy to our countryside.

How can our readers support you and pick up a copy of your book?

Being well informed about the issues and being part of a reasoned discussion is key. I hope that readers of The Lynx and Us feel, once they’ve read it, they have a clearer understanding of the species and the issues around it. It’s also beautifully illustrated throughout with the stunning photographs of Laurent Geslin, whose portfolio of wild lynx images taken in Switzerland is surely the finest in Europe. I’m honoured to work alongside him. The book is now available to buy from the publisher at www.scotlandbigpicture.com/store as well as from other outlets.

Being well informed about the issues and being part of a reasoned discussion is key. I hope that readers of The Lynx and Us feel, once they’ve read it, they have a clearer understanding of the species and the issues around it. It’s also beautifully illustrated throughout with the stunning photographs of Laurent Geslin, whose portfolio of wild lynx images taken in Switzerland is surely the finest in Europe. I’m honoured to work alongside him. The book is now available to buy from the publisher at www.scotlandbigpicture.com/store as well as from other outlets.

Header image: Eurasian lynx, Jura mountains, Switzerland © Laurent Geslin