Peru’s Cordillera Huayhuash is a spectacular domain of tropical glaciers, turquoise lakes and soaring condors; but the future of trekking there, as Peter Elia discovers, is uncertain.

“Are you going to hike the Inca Trail?” asked my curious taxi driver in Lima. “Er no, I replied. I’m travelling to Huaraz tomorrow so I can trek the Huayhuash Circuit.”

I wasn’t sure whether my taxi driver had not heard of the Huayhuash Circuit or he just thought I was completely mad for attempting it. Many international travellers fail to look past the Inca Trail when it comes to their trekking aspirations in Peru, but the Andean nation contains some of the world’s most breathtaking mountain landscapes and its trekking possibilities are myriad.

Two days later, myself and a small group of UK based hikers met with our young enthusiast guides, Yummer and Renaldo. We embarked on a couple of acclimatisation days out before attempting the Huayhuash Circuit, a 130km (81 mile) loop of the eponymous mountain range. It would be a demanding two-week trek with a total of 5,700 metres (18,700 feet) of ascent.

Even these acclimatisation hikes weren’t exactly walks in the park. Both hikes would expose us to high altitudes until we eventually hit 5000 metres (16,400 feet); the maximum altitude on the circuit itself.

I found the ascent to Laguna 69 (Lake 69), both steep and demanding, but the main challenge was being able to cope with the high altitude. By the time I approached the lake, I felt an increasing heaviness in my body, like trying to run in a dream, accompanied by a headache similar to a hangover. It was concerning – would I be able to cope with this for two weeks?

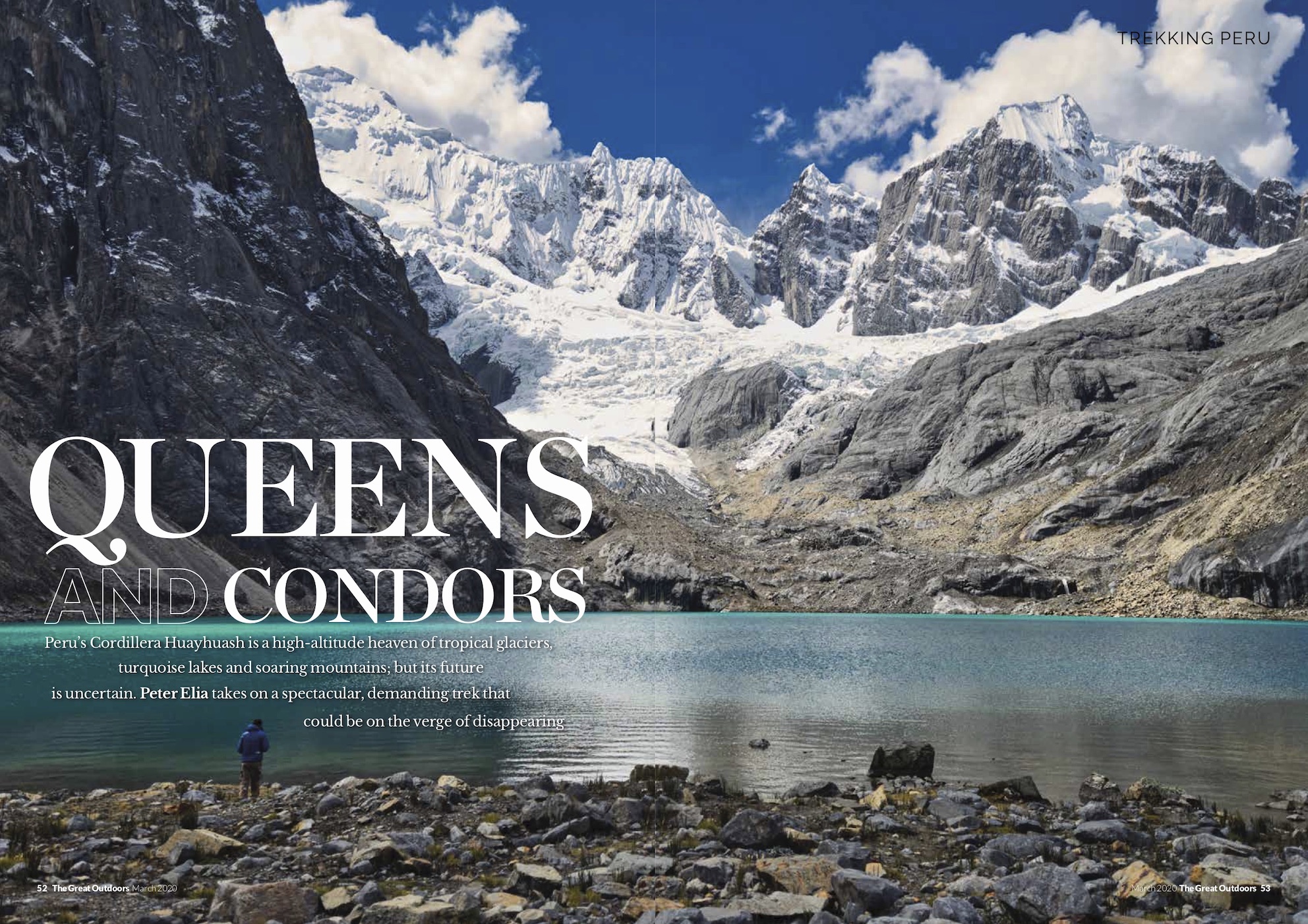

Lake Cajatambo. Photo: Peter Elia

On my weary arrival at the lake, I didn’t know whether I should rest or take some photos. But my energy levels were buoyed by the views. Oh my lord, happy days! ‘Lake 69’ is a breathtaking turquoise jewel over 4,600 metres above sea level, hugged by snowy mountain peaks, jagged rocks and surrounded by waterfalls.

Natural wonders

My spirits were often lifted by natural delights during these acclimatisation days. As well as the sumptuous views, we learned of the fantastic ‘Puya Raimondii’ plant, also known as Queen of the Andes, which is only native to some parts of Peru and Bolivia. They look like huge upside-down golden paintbrushes, with a pointed tower made up of green cones rising from a sphere of bristling pointed leaves, and grow up to 15 metres tall. They take around 100 years to reach maturity, at which point they flower once for just three months, release millions of seeds, and then die.

Huayhuash is pronounced ‘why-wash’. It seemed apt; there would not be a shower in sight for the next two weeks. Our journey would involve traversing over eight passes, all of them between 4600 – 5000 metres in altitude, with most of the walking done over 4000 metres (13,100 feet).

Starting at Pocpa, I felt both excitement and concern. This was an unknown territory both physically and mentally. I had never before hiked at this attitude nor camped continuously for two weeks. What version of me would appear at the end of this circuit? Zen-like and in tune with the natural world or broken and dishevelled, suffering from sleep deprivation or even worse – an exposure to the dreaded altitude sickness?

Puya Raimondi (Queen of the Andes). Photo: Peter Elia

The first few days eased me into the rhythms of mountain life. We would wake up around 6am, with either Yummer or Renaldo

kindly placing a cup of Mate de Coca (coca tea) into my grateful, chilled hands. The tea tasted pleasant enough and it reminded me of green tea, but there was something different about this brew; it seemed to give a welcoming boost of vitality. Yummer explained the origins of the tea were made up from the leaves of the coca plant which are also the same ones used as a source for cocaine. Yummer explained: “it’s legal in many parts of South America and an important natural plant to indigenous people. Drinking or chewing the coca leaves increase your energy and help with altitude sickness.”

Moments of joy

On the early morning of day four, with coca tea in hand and covered in more layers than a Russian doll, it was time to leave the relative warmth of my tent and head down to the Carhuacocha lake to drink in the scenery at sunrise and observe the early morning magic of the Cordillera Huayhuash as it begins to appear.

The glaciated tops of the mountains – Jirishanca, Yerupaja, Yerupaja Chico and Siula Grande – gradually illuminated and turned to shimmering gold. The light intensified further until the sun’s piercing light moved its attention to the lake. The mountains could be seen clearly reflecting on the surface water, and moments later, the water colour changed from midnight blue to emerald green as it was flooded by the sun.

I could clearly see all the shades, textures and tone of the water without polluted discolouring. The mountain air was thin but similarly clear. I took in a deep breath with exhilaration pumping through my veins a feeling of great joy in being alive. No matter how tired or cold you get on mountain journeys, these are the moments that make them worthwhile.

But despite this, the trek was about to get tougher. The middle section was the most challenging of days, involving back-to-back passes (Cuyco and San Antonio) at the 5000 metre mark, both accompanied by steep ascents. The last 300 metres (1000 feet) to the top of San Antonio felt like walking up an escalator going down. For all of my effort, I wasn’t gaining much ground. A sharp incline and loose rocks of different shapes and sizes hampered my progress.

Lake Carhuacocha just before sunrise. Photo: Peter Elia

An inspiring encounter

As the air began to thin, I felt an intense tightening of my lungs. In addition, the rocks underfoot were now becoming increasingly icy and I could see a thick layer of snow up ahead for the last 50 metres. My fellow hikers in front of me were like a young herd of Bambis on Ice and I wasn’t fairing any better.

With the last few metres were in sight, on top of my oxygen-deprived lungs, I felt sharp pains in both of my knees. At the top of the mountain saddle, too knackered to even offer up a celebratory fist bump to Renaldo, I paused with my hands on my hips, blinked the sweat from my eyes and looked up to the heavens in exhaustion.

Appearing in the sky were two blurry objects moving gracefully towards me. My first thought was that perhaps the coca tea had kicked in stronger than usual. Then I had a moment of clarity. Two condors swooped just above me majestically. Maybe they had chicks nesting close by and observed us as a danger. No matter, I was awestruck by their size, wingspan and dexterity.

As the pair of condors flew away, I was left with the most incredible 360-degree vista of every 6000 metre (20,000 feet) mountain in Huayhash. I knew there would be more challenges to come but I was sure I would able to finish the trek in one piece.

An uncertain future

As much as I revelled in the experience of this trek, when it finally came to an end it was tinged with a genuine sadness and apprehension for the future of the Cordillera Huayhuash. This is the home of the world highest collection of tropical glaciers and scientists predict they will disappear within the next fourty years.

Tropical glaciers may sound like a contradiction, but it simply refers to glaciers found between the geographic latitudes of the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. Melting ice feeds the area’s rivers and lakes. Lost glacier volumes are not being regenerated during the wet season. The knock-on effect is likely to deliver both water shortages and devastating floods which will threaten the livelihoods of two million people living in the valleys below.

Reaching the San Antonio Pass. Photo: David Weeden

I’m humbled by my experience. Huayhuash is a truly special alpine trek which lies entirely above the tree line but I also realise what is environmentally at stake. Maintaining a sufficient water supply in the face of global climate change and managing water resources in a warming world could well be the defining problem of our century.

If these glaciers would cease to exist, there would be no lakes and without lakes, there would be no condors. The spectacular mountains would still be here, of course, but many of the reasons people delight in hiking here would be gone.

I’ve been lucky enough to trek in some of the most beautiful and remote parts of the world; but for the first time, I realise that a hiking trail does not necessarily last forever.

Read it in all its glory on the page

This feature was originally published – in all its photographic splendour – in the March 2020 edition of The Great Outdoors. Read the rest of the great content in this issue – and access the rest of our archive – by ordering a back issue with free postage and packaging (in the UK) from our online shop.

Make indoor time better with The Great Outdoors

During the lockdown, we’re continuing to work (from home!) to make a magazine that will help you keep your outdoor spirit alive. Even though you can’t go physically go to the hills and mountains, we aim to take you there with our words and images, and perhaps conjure some of the feelings they inspire.

To show our readers our gratitude for their support at this time, current subscribers have had their subscriptions upgraded to include free access to the digital edition of the magazine.

To give you some great reading material for these indoor days, we’re also offering new readers:

- Three issues of the magazine along with the accompanying digital editions for £9.99 plus free postage, with no ongoing commitment to subscribe.

- Full subscriptions at just £15 for your first six issues.

- Or, if you want to catch up on content you may have missed, you can buy individual back issues with free postage and packaging.

Stay home, stay safe, and see you on the hills when the day comes!