Even the most devoted supporters of the Right to Roam campaign in England and Wales will learn and grow from the profoundly beautiful call to arms delivered by Wild Service, says Francesca Donovan.

Encased in this beautifully illustrated hardback book are some ugly truths about the state of our nature. Wild Service – brought to you by the Right to Roam movement – sets the scene with damning evidence that, in a 2022 paper published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Science examining the ecological health of 14 European countries, Britain came bottom across all metrics of biodiversity, wellbeing and nature connectedness. Our nature is hurting and, as a result, so are we.

Main image: Wild service on the River Roding | Credit: Right to Roam

The threat to nature comes not from our people but from our culture, the text – more a call to arms than a book – argues. Within the collection of essays and poetry, 13 writers share the experiences – some troubling, some tragic, all deeply profound – which have led them to understand the following fact of life: Nature doesn’t serve us, but we it. While Wild Service is an antidote to the commodification of nature through outdoor recreation, you still won’t find misanthropic tropes in these pages. Reading this will not leave you feeling guilt-ridden or ‘part of the problem’ for stepping foot on and loving our green and blue spaces. Expect, instead, to be inspired by stories of individual heroism and community action. You’ll meet rebel botanists, Peak District poets, 12-year-old butterfly enthusiasts and – would you believe – Worzel Gummidge; people “a bit rock n roll” about saving nature and a bit sick of gaudy conservation posters that seem to do no longterm good.

Of course, this is also a book about trespass. It is a debate that has sparked vitriol on social media in “tabloid style slanging matches” but in these pages you’ll find nothing but nuance, empathy, heart and soul. (“The debate is about more than fences. It’s about who belongs outdoors and who says so; it’s about Identity, class, race and gender.”) Some complain the right to Roam is a selfish movement wanting more and more land for leisure, trampling over nature. But this book – with a heady mix of our troubling history of enclosure and teachings from the 370 million indigenous people who are protecting 80% of the world’s biodiversity on 20% of earth’s land and water, thus demonstrating effective stewardship – proves them wrong once and for all. The movement stands firm in questioning the legitimacy of the singular right of wealthy men to exclude the public from nature, and the role of trespass as evidence-gathering off the wrongs being done to nature.

Even existing supporters of the movement are likely to learn a lot within these pages and explore new depth of feeling. When I read Nicola Chester describe how “we fence ourselves off and allow others to fence us out like docile compliant livestock” it felt like a powerful sucker punch to the gut. We often hear that the “countryside is a place of business” for those trying to justify their exploitation of it. But when I read sheep farmer Romilly Swann’s adamance that the risks of opening up access to nature are outweighed by the benefits (precedence for this argument comes from the church and are presented in the introduction to Wild Service) it served to quell some anxieties around the polarity within the debate.

The cairn on South Head. Credit: Francesca Donovan

I felt quite clued in on access issues regarding our natural world before reading Wild Service. And yet, I still had countless preconceptions challenged. The musings regarding cairns will be of particular interest to many mountain lovers who read this magazine. You’ll no doubt scratch your head over the reinterpretation of Muir’s Yosemite by Harry Jenkinson, as well as the homage to the rope swing, the history of our beloved bothies – a culture that began with trespassers and lock pickers – and the meaning behind the clootie trees some now consider littering.

While this book lies at the heart of where nature and science collide, it is refreshing to step away from stuffy datasets into a world in which it is okay to anthropomorphise our natural world – from peatland moss to the River Roding. Indeed, a spiritual connection to living and breathing parts of our ecology is celebrated by these folk who see ‘human’ and ‘nature’ as one and the same thing.

The authors hint at big plans for the future – a proposed voluntary national Wild Service for all young adults and a decentralisation of stewardship including Local Environmental Action Funds (LEAFs). But this, as Jon Moses declares, is “not a practical guide to overcoming the pragmatic problems of public access to the countryside…” That will come, he promises, and it can’t come quick enough.

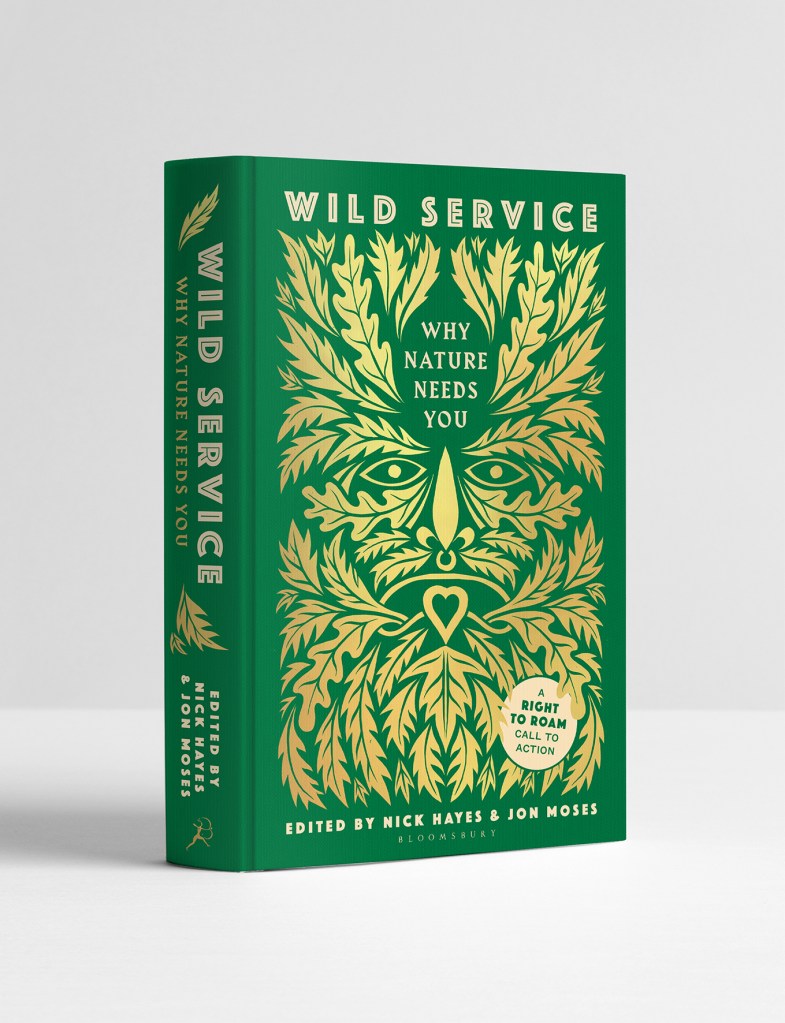

Wild Service: Why Nature Needs You is published by Bloomsbury (£20, hardback)

When contributors to The Great Outdoors aren’t out walking, some like to relax with a good book. Read their outdoor book reviews and discover your next adventurous bedtime story.