Digital tools like phones can be useful, but knowing your map-reading basics is still essential. Backpacker Alex Roddie and mountaineering instructor Helen Teasdale help us navigate the basics of reading contour lines and other map features.

A topographic (or ‘topo’) map, like those produced by Ordnance Survey or Harvey, is your passport to freedom in the hills and mountains. But all those tightly packed lines and cryptic symbols can appear daunting. The good news is that map reading for hills and mountains is not difficult to learn – and, once mastered, it can take you anywhere.

Why a topo map is essential

In our everyday lives, we navigate towns and cities with general-purpose maps that often portray the spaces in between simply as green emptiness.

But in mountainous environments, Google Maps is useless. “A topographic map gives you a good overview of the whole area, making it easier to plan your day,” Helen says. “Detail is key. A topographic map will show the relief of the ground, giving you height and shape information, and a much better overview of where the ridges and valleys are.”

A topographic map gives you all the information necessary to both plan and navigate a route in the hills:

- Lines connecting points of the same elevation above sea level. Once you learn how to interpret them, contours can help you to visualise terrain in 3D.

- Roads, paths, rights of way, streams, walls, cliffs, scree slopes, woods, lakes and more.

“I would definitely recommend going on a navigation course,” Helen says (check out those run by Plas y Brenin in Wales or Glenmore Lodge in Scotland). “Reading a map is quite an art, and being able to relate what you see to the ground is critical. Tuition will make a massive difference.”

How to choose a map

The Ordnance Survey (OS) publish a range of UK mapping; the ones to look for are Explorer 1:25,000 maps and Landranger 1:50,000 maps. Explorer maps are twice as detailed and show half the area – great for complex regions. Landranger maps lack some features such as field boundaries and walls, but give a broader view. This can be better for vast, open landscapes such as the Cairngorms. Each sheet covers a specific area; make sure you pick up the right sheet for your walk.

In many areas, Harvey offer alternative maps made specifically for walkers, with less extraneous information than Ordnance Survey, and added helpful features like colour-shaded ground and clearer contours. “I like Harvey maps because they are a little more pictorial and the contours are often higher contrast,” Helen tells us. “Harvey’s 1:40,000 British Mountain Maps are really good, giving you a slightly bigger area than 1:25,000 and removing superfluous details. The Lakes 1:40,000 sheet includes all of the main hills; you’d need four Explorer sheets to cover the same area.”

Your map also needs to be weatherproof! Some maps are printed on waterproof paper, but if yours isn’t then invest in a plastic map case.

Contours

Depending on the map, contours may be 5m, 10m or 15m apart, marked by pale orange or pink lines. Some have elevation listed. “As a mountain navigator my first priority is always the contours,” Helen says. “If I look at the ground first and then relate that back to the map, rather than the other way around, it helps me to avoid making mistakes.”

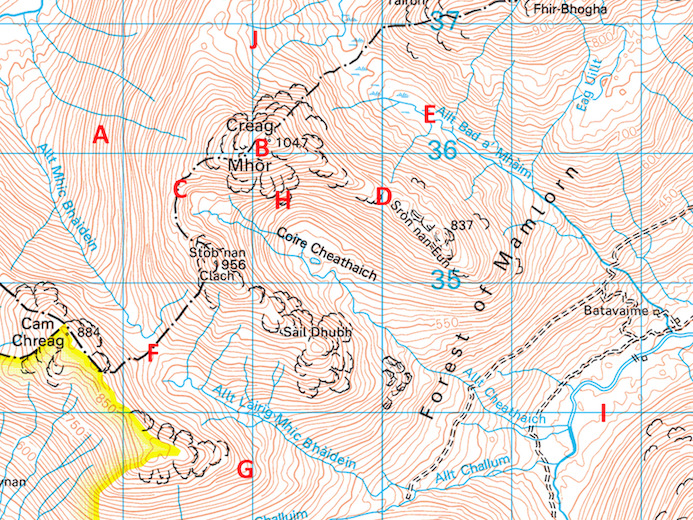

Here are some of the common contour features you’ll find on a typical topographic map (see below for the key).

1:50,000 Ordnance Survey map shown

- Slope (A, J). Contours in parallel; the closer the contours are together, the steeper the slope.

- Summit (B). Concentric contours with higher elevations towards the middle lead to a point, often with a marked elevation.

- Ridge (D, G). Represented by U or V-shaped contour lines, with lower elevations at the closed end.

- Valley (E, I). Can look similar to a ridge, but with higher elevations at the closed end and often a stream in the bottom.

- Col (C, F). A notch or saddle marked by an hourglass-shaped constriction in a ridge’s contours.

- Cliff (H). Very steep, bunched-up contours with rock features marked. Best avoided!

Features

Contour lines show you the basic shape of the terrain, but on top of this is another level of detail in the form of landscape features.

“The features walkers need to be able to identify depend on the terrain,” Helen says. “If you’re following paths then paths are pretty important! The other thing you may not realise is that rights of way will be highlighted in green, but won’t necessarily correspond to a path unless it’s also marked as a black dashed line.”

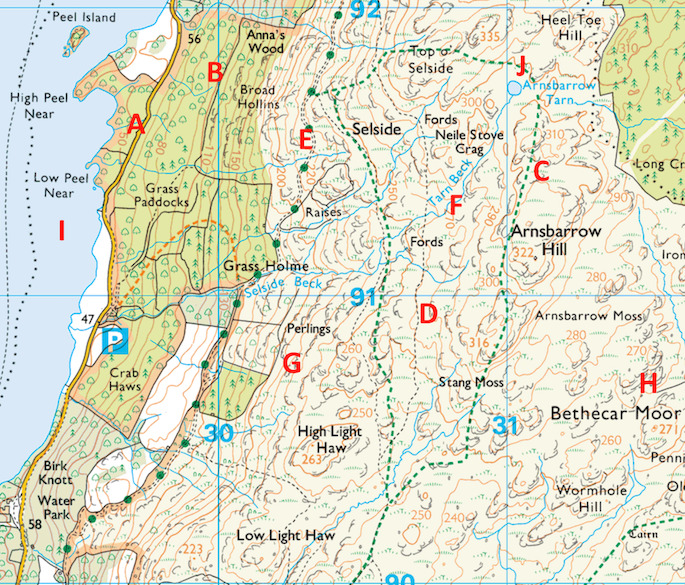

Here are some of the most relevant features walkers need to know – again, see below the map for the key.

1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map shown

- Road (A). Thicker yellow, orange or pink lines.

- Woodland (B). Green-shaded areas.

- Right of way (C). Green dashed line on 1:25,000 maps, or purple on 1:50,000 maps.

- Footpath (D). Dashed thin black line. May not be a right of way.

- Public track (E). Spaced green spots.

- Stream (F). Blue line.

- Wall or fence (G). Solid thin black line.

- Access land (H). In England and Wales, marked by orange-shaded terrain, denoting open access.

- Tarn or lake (I, J). Enclosed blue area.

Features such as woods, streams and even paths can change, leading to map inaccuracies. “Contours are a constant,” Helen says. “Using features in conjunction with contours is key. If the contours don’t fit the feature then the feature is not correct on your map.”