Fancy a challenge? Like the idea of trekking for 240+ miles through the West Highlands in winter? A winter Cape Wrath Trail could be for you. Here’s our two-part guide to planning the trip of a lifetime.

In this two-part planning guide, TGO’s Alex Roddie introduces the Cape Wrath Trail in winter and shares his tips for planning a successful and safe hike.

In this two-part planning guide, TGO’s Alex Roddie introduces the Cape Wrath Trail in winter and shares his tips for planning a successful and safe hike.

Part one covers the what and the why; part two covers the how, with a more detailed look at skills and experience, fitness, gear, and overcoming the logistical challenges.

As we publish this guide, in late April, prospective winter CWTers will be thinking ahead to next winter and starting to make their preparations. The leaves may be unfurling on the trees, but it’s an excellent time to start considering this very special British winter backpacking journey…

Contents

- What is the Cape Wrath Trail?

- Why would you want to do it in winter?

- How is the trail different in winter?

- Expectations vs. reality

This feature is part of our digital Cape Wrath Trail content. Don’t miss Alex’s feature on hiking the CWT in the May 2019 issue of our print magazine.

By Alex Roddie

What is the Cape Wrath Trail?

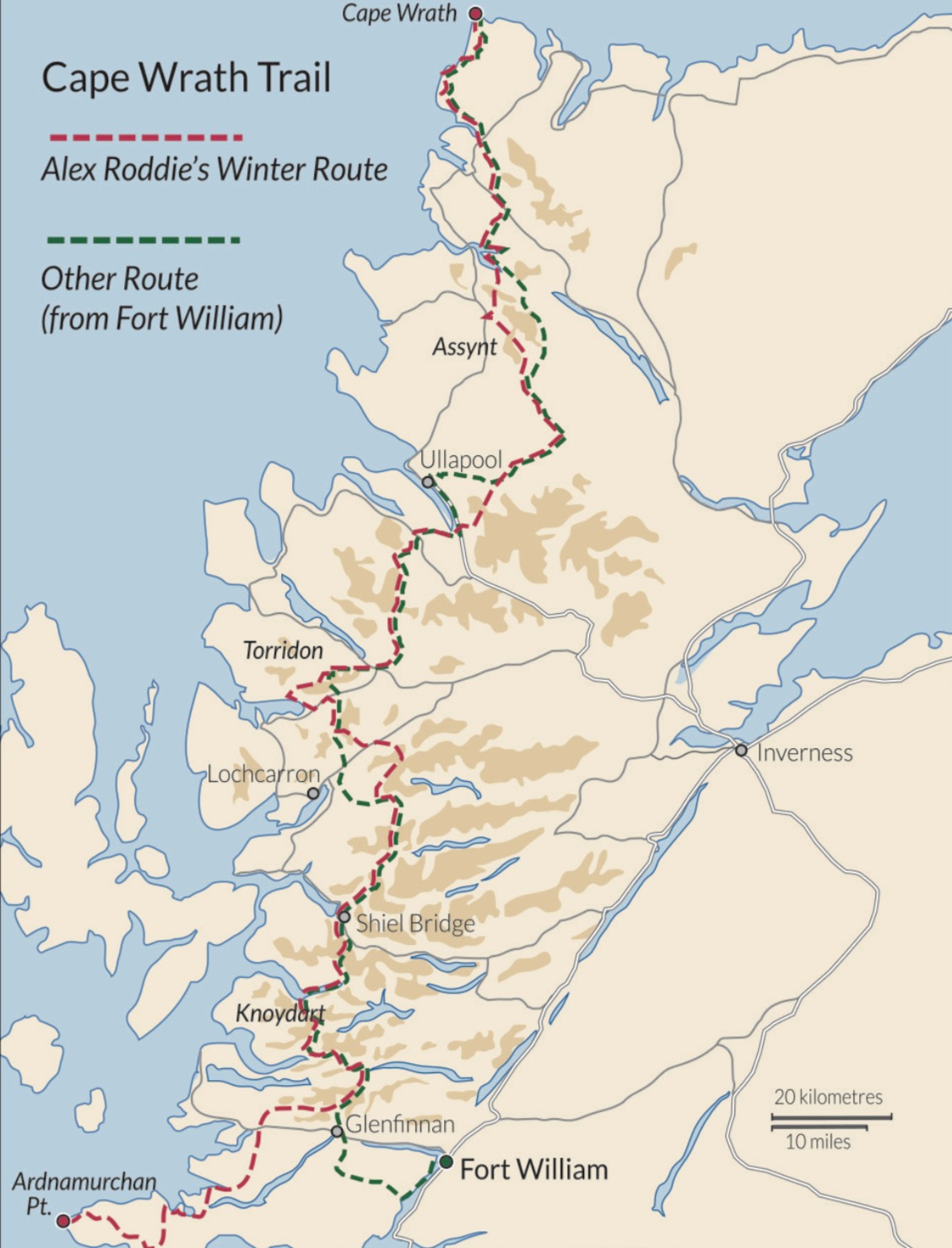

The Cape Wrath Trail is a long-distance hike stretching for well over 200 miles between Fort William and Cape Wrath, the north-westernmost point of mainland Britain.

- Looking for a quick intro to the CWT? Check out our 9 top tips here

The CWT is not an officially recognised National Trail – in fact, there is often no path underfoot at all. The route is nebulous too, giving the hiker many different optional variants to take on the way north. Highlights of the journey include a crossing of Knoydart, visits to the magnificent waterfalls of Glomach and Eas a’ Chual Aluinn, trekking through Torridon and the ‘Great Wilderness’ of Fisherfield, and the chance to experience some of Britain’s most remarkable wild landscapes. The walk finishes at the remote lighthouse at Cape Wrath.

Although standard variants of the trail don’t visit any summits along the way, this is still a long, tough walk. CWTers typically take 2–3 weeks to complete it in summer.

In winter it is a different beast. If you have the necessary skills and experience, and if the mountain weather gods smile on you, then a Cape Wrath Trail in winter conditions could just be one of the most magnificent mountain journeys you’ll ever do in the UK. But to increase your chances of success you’ll need to put in some planning and preparation.

As a starting point, I recommend Iain Harper’s excellent Cicerone guide to the Cape Wrath Trail, which I used to plan both my thru-hikes. The information in this guide should be considered supplemental to the Cicerone guidebook, which is focused on summer walking.

Why would you want to do it in winter?

Even in summer, this is one of the most serious established long-distance routes in the country. In winter it’s an even harder proposition. Before diving in to the planning, it’s worth pausing to think about why you want to do this.

You prefer the wilder, more dramatic landscape of the Highlands in winter

In winter, the Scottish Highlands seem like a bigger and more awe-inspiring place. A modest hill with a cap of snow becomes more like a mountain, and many of Scotland’s best-loved peaks become truly world class under winter conditions. To stride beneath An Teallach or Liathach on a crisp winter’s day and gaze up at cornices high above is an exquisite pleasure.

This sense of awe is about wildness, I think. With the coming of winter, humanity’s influence on the land seems to wane. Snow obscures paths, walls and fences, there are fewer walkers about, and it takes longer to get from A to B. This all adds up to a sense that the mountain environment is more resistant to human interference – that our imprint is minimal. Backpackers relish this feeling. We’ll go to great lengths to find it.

Then there are the landscape’s aesthetic qualities. The flat midsummer light is gone, replaced by a warm, directional glow that makes the landscape feel alive (if, that is, you’re lucky enough to find any sunshine). And the colours on the mountains are far more varied than in summer too. Glorious golds, browns, russets and – hopefully – whites replace the muted greens of summer. When there’s snow on the ground, the surface of the land becomes an ever-changing world of patterns and textures that’s as ephemeral as it is beautiful.

You relish the challenge

With greater wildness comes greater challenge. A long-distance winter hike is a significant test of skills, gear and logistics, and this uncertainty can translate to a more satisfying sense of adventure. Remember, though: it is not the mountain that we conquer but ourselves.

It’s the only time you can get off work

People who work a conventional 9–5 job with limited holiday might find it difficult to take a big chunk of time off during the summer. If the only time you can get a few weeks off is in February, and you have the skills, then why not consider a winter hike?

Bragging rights

Be honest with yourself – is ego a contributing factor here? Are you looking for an impressive tick in your outdoor CV, perhaps something to look good on Instagram? That’s fine, of course. I’m not going to tell you this isn’t a valid reason for wanting to hike the CWT in winter, but keep your ambitions in check – many other people have done this, and genuine winter conditions are not guaranteed.

How is the experience different in winter?

At the risk of stating the obvious here, a typical winter CWT will be a very different experience to hiking the same route in summer. The factors below contribute to the likelihood of much slower progress. The margin for error is significantly reduced and there are many more things that can go wrong.

You could be luck and find weather like this. Of course, a little more snow would be nice!

© James Roddie Photography

Weather

Seasoned backpackers in the Highlands know to expect a wide variety of weather on any trip. Foul weather can be a real problem even in summer. In winter you can expect much the same – and more. While there’s every chance that your hike could coincide with high pressure, sunshine and low temperatures, converting the West Highlands into an Arctic wonderland, it’s more likely that you’ll experience a mix of wind and rain, some snow and ice, and maybe the odd bright day thrown in there just for the hell of it.

It will, on average, be much colder than in summer, and this is another factor that could make conditions on the trail feel more challenging – and place far more pressure on your gear and clothing decisions. Driving precipitation and 25mph winds might not seem so bad at 15ºC, but at 2ºC it’s another matter, and at -10ºC it can seriously affect your progress.

Snow and ice

Common CWT variants are not really high-mountain routes. You’ll cross several bealachs at 5–600m – the highest on the ‘standard’ route is Bealach Coire Mhalagain at 699m – but there are no Munros to tackle unless you plan to take in one or two as optional extras. What this means for snow cover depends on the weather. In a typical winter, you will encounter some snow, and you may well be faced with steep slopes of snow and ice requiring ice axe and crampons. In very snowy conditions, you might find huge quantities of snow down to sea level, which could seriously slow your progress and might make you wish you’d packed snow shoes. In such conditions even very experienced winter backpackers will struggle to achieve half the mileage they might be able to do in summer.

Snow and ice can also make route-finding significantly more difficult, especially on sections where there is no path. Factor this into your planning. Make sure your nav skills are up to scratch.

Of course, you might get lucky / unlucky (depending on your point of view) and find the trail entirely snow-free, even in February…

River crossings

As in summer, river crossings are a key hazard, with the added risk that the weather could be much wetter – and the consequences of a dunking are potentially much worse. Take river crossings seriously and have foul-weather alternatives planned for the more serious rivers.

Iain Harper’s Cicerone guide to the CWT lists every river crossing on common variants of the trail, which makes it easy to plan ahead. The Harvey CWT maps show several alternative variants for most stages of the route too.

River crossings like this, partially obscured by snow pack, can be very serious. Treat them with respect.

© Alex Roddie

Most crossings on the CWT are relatively minor, but a few require knee-deep wades even in dry weather. There’s a chance you may encounter sufficiently cold conditions that these rivers are frozen and can be crossed on foot (or over substantial snow bridges), but it’s far more likely that they will be free-flowing – or, at most, only partially frozen.

Wading through deep water in freezing conditions can be risky. Every backpacker has a favoured technique, but I found the best approach was simply to cross in my boots, gaiters, trousers, and knee-high waterproof socks (which were occasionally inundated, but kept my feet warm even when wet). Your boots will probably be soaked most of the time on the trail anyway! Crossing in bare feet or legs in freezing conditions is not a good idea as you will struggle to get dry and warm again afterwards. The shock of cold water can also make you hurry to cross the river – never a good idea.

There are many bothies along the CWT. They offer a chance to dry out wet kit after a day wading through rivers. Make use of them – but follow the bothy code.

© Alex Roddie

Pack weight

All else being equal, you’ll be carrying a heavier pack. You’ll need more gear (and probably heavier gear) to cope with a wider range of conditions, and you may need to carry more food and fuel. Your daily mileage will almost certainly be much shorter than in summer. This means that you’ll take longer to get between resupply points.

In the next instalment of this guide, we’ll be covering both gear and supplies in far greater detail.

You’ll be carrying your gear a long way. Make sure it’s well-tuned to the task.

© James Roddie Photography

Daylight

This should be obvious, but it’s easy to overlook: there are fewer daylight hours in winter, which is another factor that will limit progress.

Biting insects

Midges rarely make their presence felt until well into March, sometimes much later. However, ticks are now starting to appear in some areas as early as February, especially in milder weather. I saw hundreds of ticks in late February 2019.

Expectations vs. reality

When I was planning my winter CWT, I had a mental picture of questing across pristine whiteness for days, cramponing up to the next bealach with ice axe in hand, pitching my tent on snow. I wanted it to be a real winter journey. Although I tried to tell myself to be realistic, these hopes secretly became my expectations. Surely, I thought, hiking the CWT in winter would involve all of that and more?

The reality didn’t quite work out that way. I had some great winter conditions near the start, but I also experienced more wind and rain than I’ve seen on any other trip to the Highlands – and more warm, dry, sunny weather too! If you’ve done any amount of backpacking in Scotland, you’ll know that most trips will encompass a broad range of conditions. The truth is that, in an average winter these days, you’re unlikely to find extensive snow cover down to the kind of elevations where the CWT cruises (100–400m most of the time).

You might get lucky and enjoy days of deep cold and crunchy snow, but let’s be honest – it’s more likely that your hike will take you from one island of winter to another, with a good deal of wet, dreary weather in between. This is why a degree of mental toughness is required. If you can summon the inner strength to keep going despite the weather, if you can find enjoyment in days of rain and gales – and such weather does have its own beauty – then you might have what it takes. Skills and equipment are important, but I think attitude is an even more significant factor for a route like this.

In part two of our planning guide, we cover skills and experience, fitness, gear requirements, logistical challenges, and other available resources. Don’t forget to pick up our May issue to read Alex’s feature on the trail, ‘The End of Winter’.

You can also find further material on the Cape Wrath Trail on Alex’s blog.