Even the most familiar hills always have something new to offer, as Alex Roddie discovers while walking and camping in the Dales

Start/finish: Ribblehead Station, North Yorkshire

- Leave the station at Ribblehead and head south down Gauber Road for about 1km before striking off to the right towards Park Fell’s ridge. Pass through an area of limestone pavement and two farms. The path now climbs the ridge, gently at first.

- From the summit of Park Fell (563m) grand views of Ingleborough can be seen ahead, and in good visibility the route is obvious: just continue along the ridge, circling the combe of Humphrey Bottom, before reaching the summit.

- After enjoying the extensive views, descend SW from Ingleborough’s summit and follow a good path towards Ingleton.

- Navigate Ingleton’s narrow streets, cross the bridge over the river, and climb the steep Oddies Lane towards Twistleton Scar.

- From the farm at Scar End, the path leaves the road and zigzags steeply up through limestone pavements studded with gnarled trees.

- Follow the long and gentle ridge towards Whernside’s summit.

- From the summit, descend due N at first then head E before Knoutberry Hill. A good path takes you down to the railway line. Follow the path beside it back to Ribblehead.

This feature was first published in The Great Outdoors, March 2017

Ingleborough is the place where I first learned the meaning of the word mountain. The year was 1994, and I was eight years old on a family holiday in the Yorkshire Dales. According to my dad’s diary, we walked up through woods from Clapham and visited Ingleborough Cave. But I don’t remember the caves; I remember the mountain above, so similar to the other hills nearby yet undeniably different. Even at that age, an instinct in me said ‘yes, this one is a mountain’ when I looked at Ingleborough. I’ve never forgotten that.

My hillwalking ambitions first flowered in the Yorkshire Dales. From those early steps to exploring the moors above Reeth and Kettlewell, I came to know the Dales years before I set foot in Scotland or on the Lakeland fells. As an adult, I return a few times most years – but I’m always struck by the contrast between the fresh and the familiar, new experiences and old memories.

Ingleborough has become a favourite mountain, a treasured friend, but in all my years wandering the Dales I had never set foot on Whernside, its neighbour. I decided to plot a circular winter walk taking in both summits, beginning and ending at Ribblehead Station. With no snow on the ground and a fine forecast, I was looking forward to distant views from a high wild camp.

It was late in the day and the weather looked surprisingly bleak when I arrived. I’d been unsure whether to walk my route clockwise or anticlockwise, but decided at the last minute to climb Ingleborough first. That meant my first camp would be on the slopes of Park Fell – a 563m shoulder directly above Ribblehead. As I squelched through bogs in the gathering dusk, leaning in to a bitter headwind, the ground felt deeply unfamiliar and I started to question whether this route would be as friendly as I’d imagined.

After a night of wind, I woke to a colourless dawn. The light soon returned as I began the ridge walk over Simon Fell. I’d never approached from the north before, and my pulse quickened when I saw Ingleborough’s distinctive stepped summit peeking over the boggy moorland, which was now painted in intense hues of russet, gold and green by the dawn light. There’s a deep satisfaction in approaching a beloved mountain from a new angle. Different perspectives refresh memories in the mind, like the rays of a candle tracing new shadows in a room, revealing hidden corners. I knew Ingleborough for its craggy ramparts, its square-jawed profile; until that day, I didn’t know it for the vivid greens of its bogs, or the windswept texture of grasslands on the western flank of Simon Fell.

When backpacking, there are often low-level stresses working away in the back of your mind. How difficult will that river crossing be? Do I have enough food to get me to the next town? Will another thunderstorm roll in this afternoon? What about unexpected sections of scrambling? Over the last year I’d done a few routes with such pressures, and although they had other compensations, sometimes all you want is to relax and enjoy the outdoors. As I soon discovered, my circuit of Ingleborough and Whernside was about as relaxed a route as you’ll find in the British hills.

With excellent visibility and a good path ahead, navigation became a simple game of occasionally glancing at the map to check my progress. Soon I was back on familiar ground and I grinned as I came to the rough, steep terrain climbing to the plateau from the saddle north-west of the summit. Striated boulders jutted up from the ground, part of the walls – I imagined – of the hill fort that some say once crowned this mountain.

I’ve always found the summit of Ingleborough a strange place. Although this fell has had symbolic meaning for me since childhood, and it appears as a backdrop in countless memories and photos, I didn’t actually tread on the summit until a few years ago. Perhaps this is why Ingleborough isn’t at all about the summit for me. I skirted the shelter and made for the edge, where I paused, looking north to Whernside, the highest of the Three Peaks.

Thousands of years ago, I’d have been standing on a shattered tor of rock overlooking an ice sheet. Just over four miles due north I’d have seen Whernside’s crest jutting out of the white glare. These mountains have been brothers for aeons; Pen-y-Ghent, the other Three Peak, feels like the outlier. But, back in the present day, Whernside was completely new to me. I’d never climbed it, never set foot on it, and don’t remember even noticing it during my visits as a child.

My original plan had been to stop for a pint in Ingleton before starting the next climb, but I wanted to get back into the hills. After finding my way through the alleys of the little town – the most complicated navigation I’d had to perform all day – I began the walk up through sunlit woods to Twistleton Scar. Birds sang from hazel coppices and it felt more like spring than winter. Vague memories, impressions, protruded through the fabric of my thoughts. Stomping over limestone pavement wearing wellies and a plastic cagoule, looking for fossils. Taking pictures with a cheap compact film camera. Perhaps now, as a thirty-year-old man, I am acting out an echo of those events, reconstructing my own past as I climb up to the limestone pavements yet again. The truth is simpler, of course: being a child in the Yorkshire Dales was a formative period of my life.

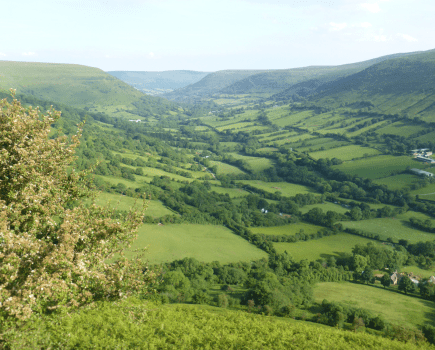

Twistleton Scar, a promontory of rock at the extreme south-west end of Whernside’s long ridge, is a magic place. There are expansive views down into two valleys and across to the rough slopes of White Scar and Keld Head Scar, but its true attraction is the network of limestone pavement where the terrain levels off. Here, the landscape folds in on itself. The crumpled topography of the Dales is replicated on a tiny scale in a complex world of clints and grikes.

I spent time wandering the limestone pavement, poking my nose into the miniature forest of mosses, lichens and ferns it nurtured. So often when backpacking I have my eye on the clock – so often I don’t take the time to slow down and really look at my environment. But on that afternoon I lingered, watching the colours sweeping across the moor and observing the gnarled old thorn trees leaning away from the prevailing wind. I crouched down and examined the patterns in the ice on the bogs at my feet.

Once again, navigation was not a concern as I climbed Whernside. That long, gentle ridge would be easy to follow even without the stone wall that guided me along its crest. As I climbed, views of Ingleborough unfolded – a new aspect of the mountain for me, yet its silhouette was still so familiar.

I camped on a flat knoll just beneath the summit. Silence and calm spread over the land as the light turned gold. Despite the plummeting temperature, I stayed outside, taking photographs at first and then just observing. Never before had I watched sunset light play on Ingleborough’s flanks from high on a hill. Whernside is the perfect vantage point for viewing its twin, its sibling across the dale – and although Ingleborough gets all the glory, Whernside has all the views.

It was a cold night, down to -7˚C. Ice crackled inside my tent when I woke for the dawn. I pulled on trousers stiffened by frost, flexed my frozen shoes before I could put them on, and packed away my camp. Ice had thickened on the puddles at the side of the path overnight; a few old patches of snow lingered, iron-hard, in the lee of the wall. I had the summit to myself when I climbed the last few yards to the top.

As I descended back towards Ribblehead, through boggy moorland criss-crossed by stone walls, I met a bikepacker who had been touring Dentdale and had camped in the valley bottom overnight. Like me, he knew the area well; like me, he visited regularly but infrequently. ‘I’ve always loved the Dales,’ he said. ‘No matter how well you think you know this place, there’s always something new to discover.’

All images © Alex Roddie